With Trump’s presidency on the horizon, US-Pakistan relations need recalibration, moving beyond misperceptions, nostalgia and emotional bias, towards a pragmatic, interest-driven approach.

Let me start by saying that US-Pakistan relations are normal. What isn’t normal, however, is Pakistan’s perception of this relationship.

Having said that, how we view and understand this important but difficult relationship needs to be “normalised”, especially as a new American president takes oath. In Pakistan, and much of the world, there are uncertainties and apprehensions as to what Donald Trump’s second tenure would mean for US global conduct and policies.

Over the past several decades, much emotion has been attached in Pakistan, for or against, its relations with the US, making it arguably one of the most talked about — yet one of the least understood — relationships.

What Pakistan needs to understand is where the relations stem from and where they stand. Otherwise, we will have unrealistic expectations or unnecessary fears that could affect the quality of our policy responses. The fact is, the transactional US-Pakistan relations will now be in the hands of the transactional Trump. This makes it all the more important to remain grounded in reality, as an emotional approach to the relationship will not work.

From anti-Americanism to a fixation

Before doing anything for any country, Trump wants to know what it can do for America. He believes in the dictum, “show me the money first.” We should be cautious about what we promise and why. And certainly not go overboard in ingratiating ourselves with Washington, like we have often done in the past. This means we should try to understand how the US and Pakistan have treated each other historically, and how the relationship is seen in many the different ways by various segments of the Pakistani population. The lack of a national consensus on these relations makes them even more susceptible to misunderstandings.

A myriad of factors reflect and influence our understanding of the US-Pakistan relations. The public view of the ties tends to be marked by anti-Americanism. Meanwhile, the perceptions of the political leadership and the foreign policy establishment, shaped partly by a dependency syndrome and partly by an addiction to the relationship with unrealistic expectations rooted in a bygone era, tend to be too rosy. Not to mention the elite’s fascination with the West.

As for the media and the strategic community, the majority opinion straddles across these two viewpoints — harbouring anti-Americanism while still hoping for a revival of the “great days” of US-Pakistan relations. And finally, the PTI supporters who, on top of the pervasive anti-Americanism that they share with the general public, have their own grudge against Washington for allegedly conspiring to remove Imran Khan’s government through a no-confidence vote.

It is hoped that a more nuanced understanding of the relationship would lead to the “normalisation” of the various impressions surrounding them, making the public perceptions a little more positive, and the official expectations a little less illusionary. In doing so, the gap between the public and official takes of the relationship would narrow, which is important for the success of any major public policy issue.

Let me say at the outset that while much of the criticism of US policies that underlie anti-Americanism is valid, it is often exaggerated or based on misperceptions. Let us look at the high-profile US-Pakistan relationship during the Afghan Jihad of the 80’s. While it is true that the jihadism spawned by that war — particularly its franchises and offshoots — has since wreaked havoc in Pakistan, it is essential to remember that the Afghan Jihad was a joint creation of the US and Pakistan.

Pakistan had the choice of dismantling the jihadist infrastructure upon Soviet withdrawal and America’s exit. Instead, we chose to adopt it for our own strategic purposes. We became its single parent. We cannot legitimately claim that the Americans left behind all this chaos for us to resolve.

In all honesty, we must accept our share of responsibility for our own destabilisation. We cannot legitimately claim to be victims of terrorism without disowning all the militants. “Good or bad” — the Taliban are part of the same network or, as the saying goes, two sides of the same coin. The Pakistani Taliban would not exist without the Afghan Taliban, and the latter would not be where they are today without Pakistan’s support. That is the uncomfortable truth.

As for the post-9/11 wars, they were not imposed on us. We willingly became partners, both in the Afghanistan war and the war on terror, in exchange for the legitimisation of the Musharraf regime, and for economic and military assistance. While the regime benefited, the national interest was served only marginally. In fact, Pakistan arguably lost more than it gained. Whatever the case, you cannot place all the blame squarely at America’s doorstep.

The cipher without a conspiracy

Finally, the cipher conspiracy. Washington has dealt with Pakistan for nearly seven decades, primarily through the military, and has intimate knowledge of the country’s domestic political dynamics. As the move to remove Imran Khan’s government through the no-confidence vote gained momentum, speculation was rife that the security establishment had some part to play in it — just as it had played a role in repeated political changes since the revival of the democratic process in 1988. This was a familiar playbook, surprising to no one in Pakistan.

So, why should it be a surprise to Washington? If the past changes could happen without Washington’s consent, help or instigation, why was this time any different? Did anyone blame America then? So, why now?

The rift between General Bajwa and Imran Khan was not an overnight fallout sparked by some abrupt directive from Washington. The establishment’s relations with the government had been fraying for some time in full public view. From past experience, we know where such tensions lead. Americans did not have to lift a finger. The tide was already turning in their favour — long before US Assistant Secretary of State, Donald Lu, met with Pakistan’s former ambassador to the US, Asad Majeed Khan. By then, it was clear to Washington that their nemesis was on his way out. So much so, Lu abandoned the usual veneer of diplomatic restraint and spoke openly about future relations the very next morning.

If this were part of a conspiracy, would Lu really have been so blunt, especially when the government hadn’t even collapsed yet? Think about it.

The grievances of PTI supporters are genuine and understandable, but their suspicion of Washington’s role in Imran Khan’s ouster stems from a misreading of how Pakistan’s system operates. Now, their hope that the US might intervene on Imran’s behalf reflects yet another misperception — this time, of how America works.

Washington will not intervene for one simple reason: no critical US interests are at stake in Pakistan that are being harmed by the present system or would be significantly better served by Imran Khan. In any case, Americans know their intervention would have no effect. For the US, this is a minor issue; for Pakistan’s political system, it’s a major one. Letters by congressmen are often a compromise solution — a political device strong enough to satisfy domestic constituents and tout the human rights pretence, yet weak enough to not jeopardise American interests.

The reality check

Softening anti-Americanism will be important for us to better understand the truth of US-Pakistan relations. Of course, we have a moral obligation to condemn certain US policies, such as Washington’s long-standing immoral support for Israel’s expansionism. Seventy-five years of massive US military aid and financial assistance have been the bedrock of Israel’s national power. In the latest Israeli onslaught on Gaza, Washington has been complicit in the massacre of over 45,000 civilians, primarily women and children. America’s absolute political support, especially its willful advocacy at the UN, has shielded Israel from accountability, inciting further offences and more US backing.

Unfortunately, Pakistan, particularly due to its diminished diplomatic clout, is in no position to influence Washington’s global policies. Like others, we will have to live with the US policies we disagree with. That will help us have an unemotional and less biased view of the US policies towards Pakistan that stands on its own merit. Yes, the US-Pakistan relationship has brought as much harm to Pakistan as benefit, but Washington alone cannot be held accountable for that. It was the partnership between US and Pakistani leaderships that led to policies detrimental to Pakistan. While the country may have suffered, the regimes gained.

It is also commonly believed in Pakistan that America is an unreliable partner. This is true to an extent, but largely a consequence of its domestic politics and global interests, which often clash with the local and regional priorities of its smaller allies. Washington’s on-again, off-again relationship with Pakistan is less a sign of unreliability and more a reflection of the temporary nature of its interests in the region.

As for the official perception of relations with the US, while it shares some of the public’s disappointments, it is largely marked by nostalgia for the “halcyon” days of US-Pakistan ties, when Pakistan was a recipient of significant economic aid and security assistance. The leadership, to reengage Washington’s attention, repeatedly highlights Pakistan’s potential role as a bridge between China and the US. At best, this claim is laughable; at worst, it is ignorant of the radical changes in the geopolitical landscape and Pakistan’s diminished influence.

It would aid our understanding if, when assessing the current state of relations, we refrain from using the heyday of the alliance during the early years of the Cold War as the baseline. That world no longer exists, and Pakistan is no longer the same.

It was never a strategic relationship

Any hopes our leadership may have of recapturing the relationship of the past are unlikely to materialise. A more realistic understanding of the relationship would make that abundantly clear. It would also dispel the misperception, held by both our political leadership and much of our foreign policy establishment, that the relationship was ever truly strategic.

Historically, the two countries have been allies on one issue and antagonistic on another. Even during periods of full alignment, the relationship served different purposes for the US and Pakistan. It is no surprise, then, that each side’s interests were historically met only partially, often at the expense of other important priorities.

The absence of shared long-term interests has prevented the two countries from developing a truly strategic relationship. Such a relationship would run up against other interests of the two countries. For example, it has caused contradictions in the past: on the one hand in bilateral relations, like the differences over the nuclear issue; and on the other, between their relations with other countries, principally China and India.

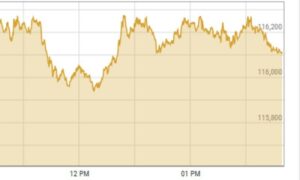

There can be no better example of the most recent contradictions in the relations than in the recently announced sanctions relating to Pakistan’s missile programme. Pakistan and the US clearly see the programme in opposing lights. For Pakistan, the programme addresses its legitimate security concerns emanating from India. As this rationale is irrefutable, Washington has injected a specious argument that the programme is a potential threat to US security. Defining the programme this way was a disingenuous attempt to maintain strategic imbalance in the region to boost India’s capability to contain China. Not to mention, to raise a red alert for the incoming Trump administration was a cheap shot if not an unfriendly act.

A necessary relationship

Pakistan’s relationship with the US is necessary, but dependency is not. There remains a future for US-Pakistan relations without being formal allies. And this should not be seen as synonymous with poor relations. In fact, it may even be beneficial. Historically, US aid has often bankrolled poor governance in Pakistan, giving Washington leverage to incentivise the elitist state to act against its own national interests.

A complete break with the US is unthinkable. Pakistan’s struggling and debt-ridden economy needs outside help, not just from China, the Gulf countries and the West, but also from international financial institutions where Washington continues to enjoy significant influence.

Our primary focus should be ensuring that future cooperation with Washington aligns with Pakistan’s larger national interests. This means fostering a normal economic and commercial relationship, as well as cooperation on shared security challenges like counterterrorism. And they need to cooperate. What each country brings to the counterterrorism strategy is complementary. And they have a mutual interest in stabilising Afghanistan.

There are also geopolitical factors. The US would like to keep a close eye on China’s growing political and economic influence in Pakistan while ensuring Islamabad does not undermine the centrality of India to its Indo-Pacific strategy. Achieving this cannot rely on a pressure campaign; it requires engagement. There is no indication from Trump’s previous tenure that he would oppose such engagement with Pakistan.

Yet, I must conclude with a note of caution. With Trump, you never know. I would not be too worried by the anti-China hawks in his cabinet or the National Security Council (NSC). In most administrations, cabinet members are valued as advisers, but Trump views them as hatchet men. His presidency is going to be a one-man show. So, it is too early to anticipate his policies towards Pakistan.

We can only hope for the best while preparing for the worst.

- Desk Reporthttps://foresightmags.com/author/admin/September 25, 2024