THE social media team of PML-N recently released a video in which a young man dressed like a cleric denounces the use of religion in politics, while the footage interspersed with his comments does the exact opposite.

The footage shows the former prime minister, Imran Khan, stumbling during his oath-taking as well as news channel coverage of the court case about his nikah with his current wife.

The video, criticised by some in cyberspace, brought back memories of the previous election, where the PML-N was on the defensive for several reasons, including allegations that it had tampered with the oath for parliamentarians.

Under attack from various quarters, the religious allegation proved the hardest for the PML-N; its leaders were attacked in public, sometimes humiliatingly and sometimes to their peril. Ahsan Iqbal, a senior leader, was shot and injured.

It goes without saying it cost them votes while the PTI whipped up the issue to gain traction.

This is not the last election in which religion is used, and neither will any party prove impervious to this temptation. And with the addition of blasphemy as an election issue, the use of religion has just become more lethal

Hence, the video from the PML-N now accusing Mr Khan of a similar ‘sin’ comes as no surprise. Not because it is accusing the PTI leader of what his party was earlier using against the PML-N but because it simply underlines the regular and constant use of religion in Pakistan’s politics.

Being the raison d’être for the formation of the country, religion has since been used by the state in particular for legitimacy and to weaken dissent or any challenge to itself. Consider the distrust of then-east Pakistanis, partly because they were seen to be not Muslim enough and hence not Pakistani enough.

Or that Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, once he had alienated his left-wing core support by turning on the student unions and workers unions, had to turn to religion to consolidate himself against his right-wing opposition. The decision to ban alcohol and replace the weekly holiday on Sunday with Friday were both made when his rule was under threat. And the account of how the military regime was hoping to discover some proof of his not being a Muslim after hanging him has recently been recounted by journalists.

The Islamisation under Ziaul Haq simply hastened this transition to the extent that since then, few have been able to avoid seeking religious legitimacy. And while religion was never far from an election campaign as a way to attack a rival, the post-Zia period saw its widespread prevalence.

Hence, while Fatima Jinnah’s challenge to Ayub Khan also led to the debate about women being unable to lead a country, this particular ‘principle’ was also used against Benazir Bhutto in her first election in 1988 after her father’s ouster.

But it wasn’t just enough to attack the Bhutto women with Islamic principles about who can be a ruler under shariat; in addition, they were also attacked for not being “good Muslim women”. The photoshopped pictures of BB, as well as of her mother, were a case in point.

This was a theme which perhaps BB had to contend with throughout her political career.

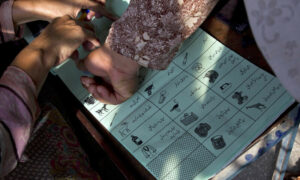

With time, and despite Musharraf’s ‘enlightened moderation’, religion has become a more potent force over time. Musharraf may have sold a different Pakistan to the West, but the one election held during his tenure as president brought the MMA, led by the JUI-F and JI, to power in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa; and while there were a number of factors at work that led to the victory, the alliance used their symbol of a book to great success. It was claimed the symbol stood for the Holy Quran and people had to choose it.

In 2008, when elections finally took place after Ms Bhutto’s assassination, Lal Masjid and the deaths of people within due to the operation were an emotive issue used by the PML-N in its election campaign to capitalise on religion and the anger against Pervez Musharraf. The next five years were consumed by violence and terrorism but once the threat was controlled, religion once again became a tool to be used in elections.

By 2018, the PTI was comfortably defending the blasphemy law and promising to protect it in a bid to paint its rival, the PML-N, as a party which was trying to weaken such provisions after the fiasco of the change in the oath.

In the months leading up to the elections, the government had made changes to the oath taken by parliamentarians, which was used by a right-wing group to accuse the government of blasphemy. Facing an onslaught from the judiciary, as well as the establishment, the PML-N had quickly caved in and its law minister had even resigned but the matter became an election issue and was used by the PTI during the campaign.

From that to the current environment, where the PML-N is the one accusing the PTI, it is an expected role reversal. Imran Khan, since he fell out of favour, has been accused of ‘blasphemy’, being an Israeli agent, having sold a watch that contained the image of the Kaaba, and getting married in violation of Islamic principles.

The list of his ‘sins’ is long, though some of them are election slogans while others have been turned into court cases against him.

This is not the last election in which religion is used and nor will any party prove impervious to this temptation. And with the addition of blasphemy as an election issue, the use of religion has just become more lethal. This is not a trend that will fall out of favour any time soon.

However, there is another aspect to this. More so that before, the growing conservatism in the society, the weaponisation of the blasphemy issue since the assassination of Salmaan Taseer and the emergence of TLP, political parties are not willing to resist any call based on religion. Nowhere else is this more evident than in the legislation in Punjab.

Despite the polarisation in the province and the hate-hate relationship of the two parties, the PTI and the PML-N, laws and resolutions with a religious aspect won bipartisan approval. Consider the law approving an ulema board to check textbooks in Punjab for material offensive to Islam or a resolution asking that the Khatam-i-Nabuwat oath be included in the nikahnama. Both were passed with support from the two parties, which were at loggerheads otherwise.

And this is at a time when the same parties at times come together at the national level to support progressive legislation.

The point here is that little of it is a well-thought-out party policy. But at the provincial level, parties and their members find it hard to resist right-wing calls, partly because of the perception that it appeals to the voters and partly because of the growing popularity of parties such as TLP, which can act as spoilers by attracting voters.

The chilling effect is hard to miss everywhere. Even in Sindh, the PPP government yielded to right-wing pressure and backtracked on the forced conversion bill, even though the province has usually led on progressive legislation such as the age limits in the law preventing child marriage.

Neither of the two trends, of resisting the urge to attack your rival with this medieval weapon during elections, and resisting right-wing pressure on legislation, is going to witness any change in the near future.

Published in Dawn, January 19th, 2024