Tracing the first decade’s events leading from one Partition — that created Pakistan — to the next — that created Bangladesh — and the role of Pakistan’s first opposition party.

The problem was a desperate one.

“We have many non-Muslims … but they are all Pakistanis,” Muhammad Ali Jinnah said soon after freedom. “They will enjoy the same rights and privileges as any other citizens, and will play their rightful part in the affairs of Pakistan.”

What was rightful and what was not, however, became contested at once, as yesterday’s majority now found itself a bewildered minority.

Because, whether it was embraced or opposed, Partition brought chaos overnight. “A Muslim comrade in the struggle for Pakistan became a foreigner because he lived in Lucknow,” wrote a British scholar, “while a Hindu Congressman living in Dacca became a loyal fellow-citizen.”

For one such citizen, the choice to stay put was a point of principle. “We, the members of the old All-India Congress Party whose lot fell in Pakistan, decided to stay in our homeland because we had fought for independence,” Sris Chandra Chattopadhyaya said. “… I told [Congress] that we would not become their sacrificial goats. We shall stay … and show to the world that the Muslims and Hindus can live in the same place, quietly and peacefully … with equal status … as one nation.”

Given a state fought and won on the basis of two nations, this was a risky gambit; the horrors of Partition — where more Muslims were massacred than Hindus and Sikhs combined — anything but its disproof.

And yet Jinnah rose to the occasion. His pledge to the minorities that they would be safe in Pakistan wasn’t just rhetoric — the dream of a founder with liberal instincts. It was also rooted in reality: that the birth of a country with an overwhelming Muslim majority (86 per cent even at that time) had removed the threat of Hindu domination for good; it was now time to make its minorities whole. With the struggle for self-determination having ended, that of national consolidation could now begin.

Hence his famous speech of August 11, 1947, no less at the inaugural session of Pakistan’s Constituent Assembly. “You are free,” said Jinnah, “you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other places of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed — that has nothing to do with the business of the State.”

Perhaps the most repeated words in Pakistan’s history, less remembered is that the Hindu leader of the opposition also spoke with cautious hope. On behalf of what would become the Pakistan National Congress (PNC), Kiran Shankar Roy said that day: “We are unhappy over this division of India … but as this arrangement has been agreed upon by the two great parties, we accept it loyally, and shall work for it loyally. We shall accept the citizenship of Pakistan with all its implications.”

A leading Bengali Congressite for two decades, Roy’s speech was met with cheers across the hall. But such goodwill was running out by the end of the session — when Liaquat Ali Khan unveiled the national flag, Congress hawk Dhirendra Nath Datta complained there was little difference between the green-and-white standard and that of the ruling Muslim League.

That first debate hence set the tone for a long and bitter exchange between the two parties over seven years, with communal undertones impossible to miss:

Liaquat: As a matter of fact, moon and stars are as common to my honourable friend, and they are as much his property as mine.

Roy: Would you have the sun also, which is also a common property?

Liaquat: The only objection is that the sun’s heat is scorching, and moon’s light is soothing. I do not want our flag to be scorching. I want our flag to give the light that will soothe the nerves.

Dhirendra: Sun indicates rapid progress.

Liaquat: We have tried to give quite a prominent place to white in this flag which I have presented. More than one-fourth of the flag is white … [which] is made up of seven different colours, and thank God we have not got seven different minorities in Pakistan. Therefore, there is room for not only all the minorities that are today but for any other minorities that might spring up hereafter.

Bhim Sen Sachar: I hope you will not create them!

Liaquat’s arguments won out — the national flag had to ‘fly in every nook and corner’ of the country just four days later so there was no time for a change. When Dhirendra moved a motion for a bipartisan committee to think up another design, the assembly shot it down.

Roy took this in stride. “I just wanted to say that after the verdict of the House,” he addressed the Quaid-i-Azam, “we accept this flag as the flag of the state. We shall pay it proper respect and we shall be loyal to it.”

This show of grace was applauded by the rest of the assembly, and a happy Liaquat turned over the flag to the Quaid’s custody.

Hardly a year later, Kiran Shankar Roy left the country for West Bengal in India, and died a few months after that. He remains Pakistan’s first leader of the opposition.

Bengal disunited

Interestingly, it was Roy’s old party, the Indian National Congress, that had authored Bengal’s partition in 1947. Along with British bureaucrats, an entire range of Bengali leaders was set against division (Roy included), with the Muslim League’s Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy wanting “an independent, undivided, and sovereign Bengal, in a divided India, as a separate dominion”. He had also told India’s last viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, that he could sway Jinnah to his cause.

But Jinnah was already swayed. When Mountbatten floated the idea of a separate, united Bengal a day later on April 27, 1947, the Quaid didn’t hesitate. “I should be delighted,” he said. “What is the use of Bengal without Calcutta; they had much better remain united and independent; I am sure that they would be on friendly terms with us.”

This was also in keeping with the original spirit of the Lahore Resolution in 1940 — that there would be “Independent States” in the plural, “as Muslim Free National Homelands” — again in the plural. No other conclusion can be drawn from the text: the resolution meant three independent, sovereign states with Muslim majorities, as Suhrawardy would propose and Jinnah would second as late as seven years later.

But while Suhrawardy pushed and pushed, the Quaid was canny enough to predict his archrivals in Congress would scuttle the Bengal scheme. On June 10, 1947, as Suhrawardy yet again rehashed his case to Jinnah on the lawns of the Imperial in Delhi, the Quaid said, “Go ahead, but the Hindus and Congress will not agree.”

He was right — they didn’t.

“I am afraid this cry of a sovereign independent Bengal is a trap in which even Kiran Shankar [Roy] may fall …” wrote Vallabhbhai Patel on May 22, 1947. “The only way to save the Hindus of Bengal is to insist on partition of Bengal, and listen to nothing else. That is the only way to the bring the Muslim League in Bengal to its senses.”

Jawaharlal Nehru was equally adamant. “The independence of Bengal really means, in present circumstances, the dominance of the Muslim League in Bengal,” he told the News Chronicle the same month. “It means practically the whole of Bengal going into the Pakistan area, although those interested may not say so. We can agree to Bengal remaining united only if it remains in the [Indian] Union.”

Just how much turned on such attitudes can’t be overstated. While citing Nehru’s interview to the Chronicle, Mountbatten shrugged to the cabinet in London that he “was afraid that, in view of this development, the prospects of saving the unity of Bengal and securing its establishment as a third dominion in India had been gravely prejudiced.”

It was the tail wagging the dog — after Nehru’s statement to the press, Mountbatten told London, “the only means by which the partition of Bengal could be avoided would be by Mr Jinnah’s abandonment of his claim to the province for Pakistan.” And even if the League foreswore the part of Bengal that had already voted for Pakistan, “the future of Eastern Bengal would present very difficult problems, since it was clearly not a viable unit”.

Confronted with this almost comical fait accompli, then British prime minister Clement Attlee’s cabinet committee “agreed that, in the event of the partition of Bengal, Dominion status could not be granted to Eastern Bengal alone; it would have to unite with one or other of the Indian dominions.”

With the British Raj having demonstrated the bankruptcy for which it was long known, Gandhi delivered the final blow. “There is no prospect of transfer of power outside the two parts of India,” he told Sarat Bose of the united Bengal camp on June 8. Not least, he wrote, his lieutenants Nehru and Patel were both “dead against the proposal”.

The stubbornness of the Congress was explained most frankly by party president JB Kripalani: with independence fast approaching, it was the land grab that took centre-stage. “All that the Congress seeks to do today is to rescue as many areas as possible from the threatened domination of the League and Pakistan,” Kripalani wrote a critic on May 13. “It wants to save as much territory for a Free Indian Union as is possible … it therefore insists upon the division of Bengal and Punjab into areas for Hindustan and Pakistan respectively.”

More than aware of this all-or-nothing attitude, the League, too, was leaving itself enough room to tug Bengal into a single Pakistan. Six years after the passage of the Lahore Resolution, the party quietly passed a new ‘Pakistan Resolution’ at its three-day convention in April in Delhi; the text cut the plural of ‘Independent States’ to ‘Independent State’.

This shift was protested by the League’s fiery young Bengali leader, Abul Hashim. The original resolution meant two independent Muslim states, Hashim argued, and a mere convention wasn’t competent to change it. According to Hashim, Jinnah dubbed the first draft “an obvious printing mistake”. The Quaid nonetheless allowed that he still didn’t want a single Pakistan encompassing Bengal, and that the original resolution wouldn’t be amended.

In any event, Jinnah’s position was consistent with what he would tell Suhrawardy and Mountbatten even after Partition had been conceded: that he supported a united, independent Bengal, just as the plural ‘States’ remained intact in the League constitution.

Besides, Jinnah fought to the end for an undivided Punjab and Bengal. “You claim the right of a large minority people to partition on a big scale,” Mountbatten huffed. “If I grant you this, how can I refuse Congress, who will press for exactly the same right for the large Hindu minorities in the Punjab and Bengal to be partitioned?”

It’s around this point that court histories mention how Jinnah was forced to accept what he had groused was a “moth-eaten Pakistan”, shorn of Punjab and Bengal’s other halves. This leaves out a fair bit of nuance: Jinnah said on April 30, 1947, that partitioning the provinces was “a sinister move actuated by spite and bitterness”, so as to “unnerve the Muslims by repeatedly emphasising [they] will get a truncated or mutilated or moth-eaten Pakistan.”

But, as Jinnah explained, “this clamour is not based on any sound principle, except that the Hindu minorities in the Punjab and Bengal wish to cut up these provinces and cut up their own people into two in these provinces.” For once, Jinnah’s logic was the same as the Bengali writer Nirad C Chaudhuri’s: that such communities were “like Siamese twins, who could not be separated without making them bleed to death” — the cold logic of division taken to a rabid extreme.

As for the trope of a moth-eaten Pakistan, the fact remains that Jinnah was going to try for all he could get; the barrister’s flourish one of many for outmanoeuvring stronger enemies. Years after Partition, Nehru’s defence minister Baldev Singh would remember the Quaid waving a matchbox at him for effect: “Even if a Pakistan of this size is offered to me, I will accept it.”

Regardless, in the crucial moment when the Bengal assembly voted, it was the Hindu members that brought division home. Per the Mountbatten Plan, a partition of Punjab and Bengal was to be carried out if a majority of any one of the two religious blocs in the provinces concerned accepted it.

That majority was found in West Bengal voting 58-21 for partition (all Muslim members voted against). “Never was so much evil owing to so few,” sighed Nirad C. Chaudhuri.

The opposite result was returned by the East Bengal assembly, which voted a thumping 103-35 against partition. That the onus lay on the Hindu lawmakers alarmed Chaudhuri: “If our opposition to the partition of Bengal in 1905 by Curzon was right, our demand for it in 1947 could not be so. But just as the British thought that their leaving India was as right in 1947 as their rule was right for two hundred years, the Bengalis thought that both their attitudes were right, each in its time. I had no doubt whatever that they were going to commit suicide.”

Doubts or no, what Suhrawardy had warned would be a ‘terrible disaster’ now came to pass. By the grace of the West Bengal assembly, a line was drawn between Dhaka and Calcutta.

Not that there weren’t exceptions: as Patel had correctly feared, Kiran Shankar Roy, then the leader of the opposition in the Bengal assembly, abstained from voting for partition. He was rewarded by Calcutta’s Hindu youths setting his house on fire.

A Pakistani Congress

With the prospect of union having receded, the weight of the Pakistan they had fought so much against was bearing down on the Congress bosses — especially those that now found themselves on the wrong side of the border. These were, in the main, caste Hindus from East Bengal.

Up against a fresh ruling class in Karachi, Lahore, and increasingly Rawalpindi, they would describe their dilemma with dark humour; as critics saddled with the wrong politics, the wrong religion, the wrong ethnicity, and the wrong language.

But much as they mocked the League, it was their preferred home, the Indian National Congress (INC), that had offloaded them. After all, it was hard to overlook Nehru and Patel’s indifference towards Bengal being cut in half, even as men as different as Roy and Bose and Hashim and Suhrawardy screamed otherwise.

To Nirad C. Chaudhuri, part of the reason this division-within-division was welcomed was because “the provinces to which the leading members of the Congress belonged were not to be affected by it. Only Punjab and Bengal, for neither of which they had much fellow-feeling, were to be its victims.”

Making matters worse was the INC’s attitude even after the fact. Despite the pleas of its Bengali bigwigs, the mother party refused to allow any offshoot to continue life outside independent India. Faced with apathy on both ends, the East Bengal leaders severed ties with the Indian body and formed a new Pakistan National Congress on August 18, 1948.

If a Pakistani Congress sounds like a contradiction in terms, some of its members felt the same way: Dhirendra Nath Datta thought it better to launch a new party with a new name — the Pakistan Gana Samiti — but worries of a split in the Hindu vote meant it acted as a proxy for the PNC, with members like Dhirendra overlapping.

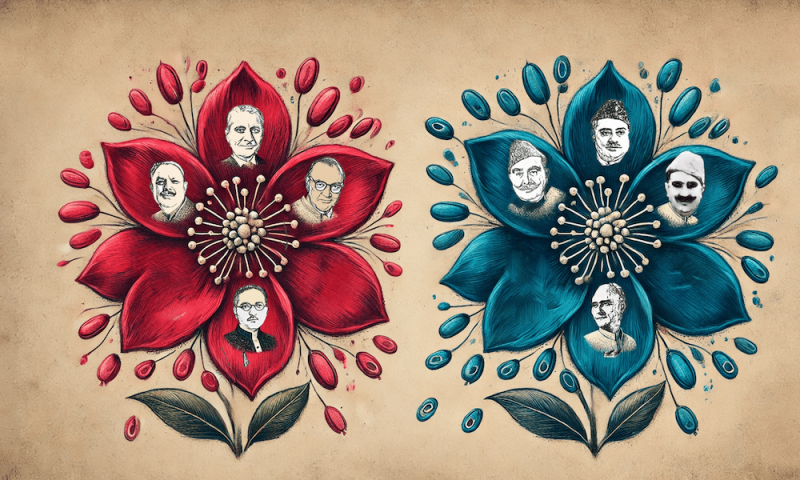

So it was that Pakistan’s first opposition party came to be. And though it has been largely erased from public memory since, the PNC remained the League government’s main antagonist for seven long years — a fact more than borne out by the parliamentary debates of the late 1940s and ’50s.

Their arena was the first Constituent Assembly, with a membership of 69 at its inauguration — or one member per a million and more citizens. The majority belonged to the Muslim League, at 49 seats; the second largest party, the PNC, at 11, formed the opposition; all had been elected by members of provincial legislatures a month before independence.

The assembly served dual functions: as an ordinary legislature, and as a body tasked with framing a Constitution for the largest Muslim-majority country in the world. While it was expected that party lines would fall away for this high purpose, that wasn’t true of real life. By dint of its numbers, the League’s supermajority meant the debates between members, while often eloquent, weren’t persuasive enough to make the difference. Nor did pushing matters to a vote — the largest haul the opposition could manage during a split was 15 (when three Muslim members broke off).

Then there was the uniquely tragic situation of being a Congress for Pakistan. Composed entirely of Hindus, the PNC quickly found the role of minority spokesperson a convenient one. But the true aim of a parliamentary opposition, as the LSE’s Keith Callard noted at the time, was to offer an alternative government for the voter’s approval. Here, the party leaders had been opposed to the idea of Pakistan, and now had to be constantly on alert against allegations of sympathy for a foreign power or, worse, disloyalty to the state — their faith only exacerbating such suspicions.

In fairness to the eye-rolling Leaguers, they had just gained a country by the skin of their teeth, and were now witnessing the PNC’s ex-colleagues in India deny Pakistan its assets, mount a brutal occupation in Kashmir, and, in Patel’s case, crow that a military solution would soon yank its errant neighbours back into the fold. There was also no small issue of PNC speeches continuing to hew close to the Indian Congress narrative, with a distaste for what Pakistan represented almost baked in.

Yet to read those debates now, it becomes clear that parliament was the scene of pushes, pulls, and polemics far more explicit than today. Though the rise of the internal party meeting was already becoming an accepted problem, there was a pointed exchange of ideas. One in which the PNC was hamstrung from the start. “A true opposition seeks to take the offensive against the government,” Callard writes. “The Pakistan National Congress had to concern itself with the defence of interests that it might yet lose.”

Helming the defence was old man Sris Chandra Chattopadhyaya, the leader of the opposition. Unlike his predecessor Roy, Chattopadhyaya was near eighty years of age and going nowhere. As a longtime advocate of the Calcutta High Court, he combined forceful oratory with a deep understanding of parliamentary procedure. And in the assembly that came to be known as the Long Parliament, he would lead his small and unhappy band of PNC walas with determination.

The Objectives Resolution

Nineteen months into its life, prime minister Liaquat Ali Khan introduced the Objectives Resolution to the House on March 7, 1949 as “the main principles on which the Constitution of Pakistan is to be based”. Calling it the most important event since Independence, the prime minister kicked off a marathon debate over five anguished days.

The resolution proclaimed the state would work through the people’s chosen representatives and observe democratic principles; that the Muslims would be able to live their lives in accordance with Islam just as minorities could profess their faiths freely; and that Pakistan was to be a federation with autonomous units, fundamental rights, and independent judges.

As has been remarked, the resolution was “merely a deposit on account”, to be accepted in good faith: the ulema hoped to enshrine the principle of a state premised on religion, while the politicians found the same principle acceptable so long as it wasn’t clearly defined.

But no sooner was the resolution moved by the League that it was scorned by the PNC. “We thought that religion and politics would not be mixed up,” said Chattopadhyaya, concluding later, “ … What I hear in this Resolution [is] not the voice of the great creator of Pakistan.“ What would he tell his people, whom he had been “advising to stick to the land of their birth? … What heart can I have to persuade the people to maintain a stout heart?”

His colleague, career revolutionary Bhupendra Kumar Datta, went further, and moved to delete the opening, which read that the sovereignty over the universe belonged to God alone, and that His authority was delegated to the state through its people, if within celestial limits.

“We on this side of the House claim to be as good Pakistanis as anybody else,” Bhupendra said. “We have lived in this land for generations unknown, we have loved this land, we have fought and suffered for its liberation from foreign yoke. We shall resent it for generations that … you condemned us forever to an inferior status.”

Professor Raj Kumar Chakraverty, more restrained than the jail-going, hunger-striking Bhupendra, wanted a subtler change: that God’s authority, as “delegated to the state”, be swapped for “delegated to the people”. As Chakraverty saw it, the wording allowed the state to wield power in any way it liked, when “a state is the mouthpiece of the people and not its master.”

One after the other, the PNC’s amendments failed. And when Speaker Tamizuddin Khan opened the floor, the League’s leading lights hit back: the resolution was defended by freedom activist Abdur Rab Nishtar, professors Mahmud Husain and Ishtiaq Qureshi, and international lawyer Zafrulla Khan.

To the charge that the Quaid would have disapproved, Nishtar responded, “Pakistan was demanded with a particular ideology, for a particular purpose,” and the resolution was in keeping with Jinnah’s pledges “to the majority as well as to the minority. We have done nothing and none of us dare to do anything which goes against the declarations of Quaid-i-Azam.”

It nonetheless became clear there were varied interpretations of the resolution within the same party: while Liaquat assured the House he sought “a truly liberal government”, Zafrulla spoke of the prohibition of usury, drinking, and gambling. To think politics was mutually exclusive from religion, claimed Zafrulla, was to take too narrow a view of religion. (As one observer noted, such views couldn’t protect the member from being dubbed a heretic two years later.)

Others stuck to safeguards. While pointing out the Islamic clauses only related to the Muslim majority, Mahmud Husain focused on restraining the leviathan; he cited a range of European thinkers had divorced morality from politics, in service of a sovereign gone wild. But “the state of our dreams shall not be sovereign without any limits,” he said.

Would the religious right agree? “How many of these learned gentlemen understood the much-abused term ‘sovereignty’ in the familiar classroom sense of deputy minister Mahmud Husain, PhD?” writes American political scientist Leonard Binder. “Erudite references to the sins of Bodin and the excesses of Machiavelli did not stir them at all.”

Such condescension missed the point: just because the rightists didn’t agree, didn’t mean they didn’t understand; the resolution could mean something rather different in their hands. This most piercing critique came from Chattopadhyaya: “What are those limits, who will interpret them?” he asked. “Dr [Ishtiaq] Qureshi or my respected Maulana Shabbir Ahmed Usmani?”

At the time at least, the ulema were nowhere at the fore of the resolution. “There is no strong evidence to show that the leaders of the Muslim League had in mind anything but modern democratic nationalism,” notes Binder. If so, it would have been even more democratic had the majority accommodated the opposition’s less radical changes in the spirit of bonhomie, rather than dismissing each one.

A divide that stark also meant the debates of 1949 have since take on the status of a grand opera; a fight for the soul of the country. In truth, the Objectives Resolution was a compromise document for a complicated project: the world’s first Islamic republic, one that could neither become a secular tent nor a theocracy of divines.

Along the way, it seems to have accomplished something democratic: condemned by liberals and mangled by conservatives (General Zia’s anti-minority edit was reversed in 2010), it remains the only tract that has formed the preamble of all three of Pakistan’s constitutions.

And it has also evolved along with them: Raj Kumar Chakraverty’s amendment, fiercely contested at the time, was accepted by the framers of the current Constitution. As the preamble now stands, God’s authority is ‘exercised by the people of Pakistan’ and not the state.

This would be referenced several decades later by the Supreme Court’s Justice Jawwad S. Khawaja striking down military courts in his dissenting opinion in District Bar Association, Rawalpindi v. Federation: “Though Professor Chakraverty was unsuccessful in 1949, our Constitution makers in 1972-73, who were fully aware of the divisive debates of 1949, accepted what had been proposed … as a fundamental Constitutional principle.”

It had only taken them three coups and a quarter of a century.

As for Chattopadhyaya, his speech would lend itself to the title of a Dawn essay by the paper’s greatest columnist, Ardeshir Cowasjee, on May 2, 2010, called ‘Not the voice of the creator’. “Jinnah’s Pakistan has virtually ceased to exist,” wrote Cowasjee the month of the Eighteenth Amendment’s passage, “but there are still some who hope it has not yet been interred forever.”

Degrees of difference

Things didn’t get any easier for the PNC in the House, as the terms of their exclusion were nuanced by some of the brightest minds in the country.

When the party protested that non-Muslims be allowed to become president, this was waved away by law minister A K Brohi. “He [the president] is only there for naam ke wastay,” said Brohi, like the powerless king of England, and incidentally, wasn’t the king required to be Anglican?

Besides, a non-Muslim could still be prime minister, just not the ribbon-cutting, party-throwing head of state. “I do not think any of my friends on the opposite [side] would like to lead a retired life like that,” said Brohi.

Chattopadhyaya’s rebuttal — that unlike the British monarch, the president of Pakistan was elected (he also wasn’t the head of a church that mandated his confession) — was never entertained.

Even more disruptive was the question of voter rolls: together or apart? Jinnah’s own famously complicated relationship with separate electorates — a battle between his ideals and his electors — illustrated the dilemma well. Or, as one critic sneered in 1946, “Pakistan is only the lengthened shadow of separate electorates.”

The importance of such electorates was rooted in anxiety: that the Muslim elector would be swallowed up by a one-man, one-vote system in undivided India. After independence, however, the majorities had become minorities, with the League in the chair. Having fought so long for special status, the ruling party was more than happy to pass on the favour to its own minorities in Pakistan.

But just as the League’s ideas hadn’t changed, neither had those of the PNC, which went right on demanding joint electorates — in an alternative universe where the numbers stood reversed.

“In my dictionary, there is no such word as “majority” or “minority”,” said Chattopadhyaya. “I do not consider myself a member of the minority community … I consider myself as one of the 7 crores of Pakistanis. I do not want any special rights. I do not want any privileges. I do not want reservation of seats in the Legislature. I say frame the same laws for me which affect everything equally.”

While this was doubtless the ideal arrangement, it was a bit removed from the situation on the ground. In the words of Sindh’s hardnosed political boss, Ayub Khuhro, without reserved seats, “not a single Hindu will be returned to the Assembly”. (Long depressed, Professor Chakraverty replied, “We want to go out of existence; that will do good to the country.”)

But the PNC kept pressing their claim, and with reason: under separate electorates, Hindu politicians could cater only to all-Hindu electorates, limiting themselves to drab communal campaigns. That also meant closing the door on national politics, as well as yet another special category — Scheduled Castes — dividing the Hindu vote.

“This party is treated with contempt,” Dhirendra Nath Datta said, “and it deserves that because, sir, we have not got the potentiality of being converted into a majority party unless there is one common electorate.”

But two years later, as Callard points out, when the East Bengal elections of 1954 had confirmed the popular mandate of many of the Hindu leaders, a final attempt was made to convince the majority. Standing by himself in the House, his PNC allies having snubbed the Constitution-making process, Dhirendra told the treasury benches, “We want to be united with you. We want that there should be one electoral roll for both the Hindus and the Muslims.”

When translated into winning votes for Hindu lawmakers in 1954, Dhirendra’s logic left a mark on another, newer party in East Bengal — as the Awami League threw its doors open for non-Muslim members.

And yet, fearful of any move that would heal Bengali divisions, the status quo suited Pakistan’s other half just fine. Social collapse would follow.

‘They are only boys.’

At the core of the problem lay the question of autonomy: if there was one quest that consumed the Constituent Assembly more than any other, it was that of a federal solution. Because Pakistan had been born a ‘double country’, two wings separated by over a thousand miles of hostile Indian territory, with yawning differences in politics, geography, ethnicity, and economy.

But the first spark was language. “The State language … should be the language which is used by the majority of the people,” Dhirendra moved as early as February 25, 1948. Liaquat promptly accused him of creating “a rift between the people of Pakistan”.

And yet Karachi’s case against Bengali, like how it was too coloured by Sanskrit, scarcely passed muster — especially given the sisterhood between Urdu and Hindi. “Bengali was not a Hindu language at all,” Chattopadhyaya told the House. “… All our books, as you know we were the custodians of our books as Brahmins, were written in Sanskrit — not one word in Bengali.”

By 1952, the high politics of the assembly had devolved into bloody student agitations in the street — at the end of the broken curfew on February 21, four Bengalis lay dead from police fire.

“They are only boys,” said Chattopadhyaya. “… Who agitated our own boys? Students of colleges! I know how to stop them.” Nurul Amin, the conservative Leaguer from East Bengal, had little patience for this; the PNC was fanning the same flames it was weeping over: “They will provoke them and tell them to go on creating chaos in the country because that suits their purpose,” he said.

But beyond this ritual exchange, the riots had completely transformed the push for Bengali autonomy, in a way the assembly — on both sides — couldn’t quite understand at the time. From the days of the Raj, Pakistan had inherited weak national parties and strong provincial outfits: slowly but surely, a new ‘vernacular elite’ elbowed past much of the old guard from Dhaka, and demanded that East Bengal’s majority be acknowledged.

Hence the rise of the Awami League, a party of small-town lawyers and students in a hurry. Before the year was out, it had triumphed not only in the provincial polls but also on the Bengali issue. Though it chided a succession of leaders from Jinnah to Liaquat to Nazimuddin for sticking to Urdu, the matter was nonetheless settled by 1954 — when the assembly’s draft Constitution enshrined Bengali as a national language.

But the riots had not only taken a toll on Pakistan as a federal project, they had also irreversibly demonstrated one of Bengal’s most powerful political traditions: the strength of the student.

Purge

As could have been predicted, the fight for autonomy soon graduated from a brawl between political parties to an all-out east-west struggle within the heart of government. Brewing since the death of Jinnah, whose paramountcy meant such tensions were kept at bay, Liaquat Ali Khan’s unsolved murder tipped the fight into the open.

Though an oversimplification by everyone from local reporters to British diplomats, it was the Punjab group and the Bengal group that drew battle lines. “Liaquat had managed to keep the major antagonists in relative balance,” writes Lawrence Ziring, “but in matters judged to be of vital importance, he was more likely to favour the Fazlur Rahman group.”

Not to be confused with the shrewd maulana, Dhaka’s Fazlur Rahman was a key cabinet member, arrayed against finance wizard Ghulam Muhammad steering the Punjab faction. Liaquat had admitted his “highest priority” was sacking the latter, a bureaucrat given to paranoia and rage. Before he could act, however, Pakistan’s first prime minister had fallen to an assassin’s bullet.

From the beginning, the Bengalis couldn’t shake the fear that Liaquat had been killed because he leaned towards the east; they also dealt in dark whispers about Ghulam Muhammad’s possible involvement. Kicking him up to the ceremonial office of governor-general, while bringing in Nazimuddin as prime minister, was thought the solution; it would prove the opposite.

“Throughout the first quarter of 1953, the governor-general made several unsuccessful attempts to persuade the Prime Minister to reconstitute the cabinet,” writes scholar Yunus Samad. “He wanted a surgical action which would remove Fazlur Rahman, Nishtar, Mahmud Husain and Sattar Pirzada from the cabinet and leave the pliable Nazimuddin in place …”

Given these were also the ministers “most difficult for Ghulam Muhammad to control”, per author Allen McGrath, it would be a mistake to think the governor-general was motivated by visions far grander than personal power at the assembly’s expense.

Nor was the fight purely ethnic in nature: as another writer has noted, the Bengal group had non-Bengali ideologues (Abdur Rab Nishtar and Mahmud Husain), and the Punjab Group had non-Punjabi soldiers (Ayub Khan and Iskander Mirza). The former sought its strength from a parliamentary majority; the latter from an increasingly powerful nexus between generals and bureaucrats. That was, as always, the principal contradiction, though British cables do much to caricature the former as elected conservatives, and the latter as liberal technocrats.

In fact, the two factions clashed across the board: in matters foreign, Ghulam Muhammad and Ayub were more than eager to commit themselves to the Americans and their military pacts. While suspicious of the Soviets, the Nazimuddin ministry wasn’t quite as enthused about Uncle Sam. On the domestic front, the growing confidence of the Bengali majority was upsetting to the Punjab, just as the stridently non-Bengali civil service saw the government as weak and vacillating.

Over the next several weeks, as spring set in and anti-Ahmadi riots engulfed Lahore, Ghulam Muhammad’s men took their chance. The contrast between a responsibility to the public — however distant — and the joys of unelected force, was brought out by Iskander Mirza’s recently published memoirs recounting the episode on a single day in March.

As Nazimuddin was being persuaded to surrender to the rioters by a prime enabler himself, Punjab’s chief minister, Mumtaz Daultana, Mirza put in a call to major-general Azam Khan in Lahore. “I take all responsibility,” Mirza told Azam. “… Declare martial law, take action, and finish the thing off.”

“Sir, there will be casualties,” said Azam.

“I expect casualties,” the author cheerfully reveals. “Or you will not be doing your duty.”

As the soldiers rushed to take Lahore from the sectarians, the major-general’s updates began grating on Mirza: “Azam Khan started to send me telegrams — with a copy to the prime minister — stating: “X number mullahs shot today.” At this, the prime minister went off the deep end. He called me and moaned, “Colonel, I cannot sleep.’”

Mirza’s solution to this surreal problem was to have Azam amend his letters to “So many bad characters shot.” After that, Mirza writes obliviously, “[Azam] used this formula, and everyone was happy, except perhaps the mullahs. And this was how we were running the country.”

Scarcely more material is required to understand the thinking of this most early of deep states. “The governor-general used to send for me and say: ‘How can we run the country with this prime minister?’ admits Mirza. “I used to keep quiet. What could I say?”

The ‘we’ — Ghulam Muhammad, Mirza, and Ayub — all strong personalities (the latter two with zero votes to their name), was illustrative. And with law and order returning to Lahore (“Damn good show,” Ayub congratulated Azam), Ghulam Muhammad launched Pakistan’s first successful coup. What Mirza described as a “fight to the finish” between conservatives and liberals — buffeted by Ayub urging a change in government if the army’s confidence was to be maintained — meant a major purge.

Not that it had any legs: the riots had been quelled, the budget had just been passed, and Nazimuddin had refused the rioters’ core demand — that foreign minister Zafrulla step down. Most of all, he enjoyed the support of the majority in the assembly.

It’s also why the cabinet’s Bengal group defied Ghulam Muhammad’s orders to resign, rightly claiming the parliament’s confidence. As expected, the ministers who were purged along with Bengalis Nazimuddin and Fazlur Rahman were the same deemed most problematic by the unelected: Nishtar, Sattar Pirzada, and Mahmud Husain, “replaced by three figures with little political strength.”

This was thrown in sharp relief when the governor-general reappointed half of Nazimuddin’s cabinet — including the embattled Zafrulla.

The true arrival, of course, was that of the soldiers in the palace. The governor-general “could never have dared to dismiss a ministry which had appointed him, had he not have had the support of the army,” Suhrawardy wrote that week.

Per their own cables, the coup seems to have been met with satisfaction by British officials. As Nazimuddin desperately tried to call the Queen and have her governor-general reverse himself, London held that a sacked prime minister “has from time of dismissal no right of access to the Queen, who could only be advised by Ministers in Office”.

Not that it ever got that far: Nazimuddin’s phone line had been cut.

Eclipse

Though claimed otherwise at the time, the illegal removal of Pakistan’s second prime minister was not without consequences.

As even the British High Commissioner cabled to his superiors, “Khwaja Nazimuddin was an East Bengali and East Bengal’s leading political figure. He had now been brusquely and possibly unconstitutionally, dismissed, and without consultation with political leaders in East Pakistan.”

And though the newly installed premier, Muhammad Ali Bogra, shared Nazimuddin’s ethnicity, feelings in the East had begun to boil over.

Less than a year later, the Awami League’s United Front alliance swept the provincial elections. Comprising Suhrawardy, Fazlul Huq, and peasant leader Maulana Bhashani — with derision for the Muslim League the main factor in common — the Front had campaigned on a platform of Twenty-One Points. Easy to see now as the Six Points in embryo, the manifesto vowed the regional autonomy promised in the Lahore Resolution.

The result was a thrashing for the Muslim League. ‘Sher-e-Bangla’ Fazlul Huq was elected chief minister, but the lion’s roars to the press — invoking the province’s ‘independence’ — alarmed Karachi.

Nor did soaring violence help: taken together, the coalition barely lasted six weeks in office. In yet another first, the west resorted to direct intervention in the east on May 29, 1954 — the Front was sacked and emergency rule imposed under Iskander Mirza with Bogra calling Fazlul Huq a ‘self-confessed traitor’ for good measure.

As Bengali leaders fell one after the other, the east’s serial humiliations had started to overwhelm the entire country. In one extraordinary session of the Constituent Assembly on July 17, the PNC even made common cause with the Muslim League’s Mahmud Husain — late of Nazimuddin’s ruptured cabinet — in slamming emergency rule. “The paradox in East Bengal is that on the one hand we call ourselves a democratic state … but a province which consists of the majority of its population has been denied the democratic right to govern itself,” Husain said.

And in more places than one: “If one went to the East Bengal Secretariat, one was surprised not to find a single Bengali Secretary in the whole of the Secretariat,” whereas the west’s civil servants “are hardly on meeting terms with any of the Bengali officers”, and that hatred and suspicion began seeping in as soon as Partition.

Faced with a member of Mahmud Husain’s nationalist credentials, an ex-chief whip no less, taking aim at the centre’s neglect, Bogra’s allies attempted to mitigate their embarrassment. But when the deputy speaker headed off Mahmud Husain mid-speech, support came from unlikely quarters:

Sris Chandra Chattopadhyaya: I can give five minutes from my own time. He should be allowed to continue.

Bhupendra Kumar Datta: He is speaking the truth.

(Interruptions by several members)

Bogra: The Honourable Leader of the Opposition has let the cat out of the bag.

Shri Sris Chandra Chattopadhyaya: Yes, he has exposed you thoroughly by naked truth.

Members from Opposition benches: He is speaking the truth. He is speaking the naked truth.

… Shri Sris Chandra Chattopadhyaya: …I tell my friend Dr Mahmud Husain that of all the Muslim members of the Muslim League party who spoke here, he has said the truth and reality which others had not the courage of doing … Mr President! Sir, I stand here not for the purpose of vindicating Fazlul Huq’s ministry … but I stand here to vindicate the rights, the valuable rights, of the people of East Bengal. I stand here to vindicate democracy.

Bogra was unfazed — he blamed much of the problem on communism and his speech received flattering Cold War-era coverage in the New York Times.

But along with shifts in the assembly, 1954 marked a turning point. “The Punjabi leadership … was quick to realise the implications of the fundamental change brought about in the polity by the defeat of the Muslim League in East [Bengal], and the unanimous vote in favour of provincial autonomy,” writes Hasan Zaheer in The Separation of East Pakistan. “The solid bloc of Bengalis in the parliament could easily woo the smaller provinces and thus dominate the Punjab.”

Bogra was in the midst of this slow realisation, even as the assembly’s dissidents were planning a shock of their own. The League rebels (a broad church led by Fazlur Rahman and shepherded by speaker Tamizuddin, along with Nazimuddin, Mahmud Husain, and, ironically, AK Brohi were able to marshal enough numbers for a majority and, on 21 September, passed the Fifth Amendment — stripping the governor-general of his powers via a lightning raft of bills.

As Callard writes, the thesis was simple: ‘The arbitrary action of the governor-general in dismissing the Nazimuddin ministry had been neither forgiven nor forgotten.’ The ‘rebel tactics’ had four aims: to repeal PRODA (the not-so-venerable grandfather of the NAB Ordinance) and prevent the governor-general from prosecuting the assembly’s members; to deprive the governor-general of his powers; to bring in a no-confidence button; and to restrict future governments solely to members of the assembly, ensuring the cabinet’s dependence on the legislature.

It wouldn’t have been premature to say this was a political settlement in the offing: that at last, the assembly could be sovereign; at last, a federal structure could be agreed upon; and at long last, a draft Constitution of 1954 had been approved and was making its way to the printers, to go into effect on the Quaid’s birthday on December 25.

Of course, Ayub prevailed, and another coup followed on October 24, 1954: the draft Constitution was stillborn, the assembly dissolved, and the Long Parliament breathed its last. Ghulam Muhammad’s new ‘cabinet of talents’ — with defence to Ayub and the interior to Mirza — set the stage for the Constitution of 1956, one that went much further in empowering the president, under-representing the Bengalis, and earning the outright rejection of the Awami League.

A month later, Fazlur Rahman was confined to East Bengal, by order of the government under the Security of Pakistan Act. He was subsequently disqualified from politics by Ayub’s EBDO law, the successor to PRODA.

Prospect

To the critics, the story of the first Constituent Assembly is a story of decline — its members too lazy and too divisive to have been up to the task of framing a country’s Constitution.

It’s a diagnosis that lets the real culprits off too easy, per Dawn from three years later, “There have indeed been times — such as that October night in 1954 — when, with a general to the right of him and a general to the left of him, a half-mad governor-general imposed upon a captured prime minister the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly and the virtual setting up of a semi-dictatorial executive.”

Even still, while the Long Parliament did take its sweet time, the draft Constitution of ’54 had no small number of achievements: it accepted Bengali as a national language; afforded the east its numerical majority in the House; allowed for a Senate as part of a bicameral system; tried the flawed but workable Bogra formula as a means to pull along both wings in federal fashion; left the window open for a prime minister from a minority faith; declawed the governor-general in favour of the prime minister and parliament; and dismissed the idea of One Unit out of hand.

Few of these proposals came naturally, and almost all merited more debate. Yet it bears repeating that the October coup set off a horror house of events for East Bengal — from delayed polls to One Unit to another takeover in 1958: with the assemblies sacked all over again, political parties (including the long-suffering PNC) banned, and a dictatorship of the army declared.

When general elections did resume, the much-persecuted Suhrawardy was gone; his place taken by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, a violent provincial that harbored none of the pretensions to all-Pakistan leadership his late mentor had.

Meanwhile, Ayub handed East Bengal to Nurul Amin’s cruel and reckless protégé, Monem Khan. Unlike his predecessor Azam (whose career took him from martial law in Lahore to a popular stint at the Governor House in in Dhaka), Monem arrested journalists, rigged elections, and even banned Tagore — he would also taunt Fatima Jinnah’s supporters for not having nominated an East Pakistani as their presidential candidate.

The breakup that ensued is beyond the scope of this piece, but half a century is long enough for today’s scholarship to take alonger view than just the sins of three men: Yahya, Bhutto, and Mujib. The conservative take — that Indira Gandhi’s scheming and Mujib’s treachery came together to overwhelm Pakistan, by then a helpless victim of the maniac Bhutto and depraved Yahya — ends with friendly foreign powers abandoning the country at the crucial moment.

The liberal approach is more thoughtful, if not thoughtful enough: the gross theft of the Awami League’s mandate, the postponement of the Dhaka assembly, General Tikka unleashing war crimes on a civilian population from March 25 onward, the failure to find any political solution in the interim, and the abandonment of the Polish resolution at the United Nations.

In fact, the threads that unraveled that December went all the way back to the promise of the country’s creation. Given what we see today — from Balochistan to the former tribal areas, and from Azad Jammu and Kashmir to Gilgit-Baltistan — it is high time Pakistanis honour the federation that remains, as well as each one of the minorities that continue to call it home.