‘Swing constituencies’ are those that can be won by influencing very small changes in voter preferences.

“Thus do many calculations lead to victory, and few calculations to defeat” — Sun Tzu, The Art of War

GIVEN the complexity of Pakistan’s electoral dynamics and unpredictability of the role the various ‘external’ stakeholders may play in it, there have been very few instances in the country’s democratic history when any party has been so confident in its chances that it has relied on campaigning alone to win itself an election. In reality, despite having all the appearances of a rowdy public brawl, every election has been played like a game of chess.

Most ordinary voters may not realise this, but every political party fights an election on two fronts. The first is the performative one; one that requires prominent faces to strut or weep on stage and woo voters with outlandish promises and/or seductive ‘bayaania’ (narrative, if you so prefer). The other is a quieter one; one fought by electoral ‘scientists’ — people who know the ins and outs of the electoral process — who work behind the scenes to ensure their party is in a position to win even before the first vote is ever cast.

With the combined effect of these two strategies, all parties aim at sweeping into power with comfortable margins in as many of the constituencies they are contesting from as possible. Realistically, it is impossible to win everywhere, and they know it; however, with the help of data, they can convert past defeats into future victories. This is where ‘swing constituencies’ and strategies to flip them come in.

‘Swing constituencies’ are those that can be won by influencing very small changes in voter preferences. In Pakistan, every election throws up a considerable number of ‘swing constituencies’ that may have gone to either of the two top contenders if voting patterns in those constituencies had been just a little bit different.

Political analysts usually use a five per cent margin of victory as the yardstick when calculating whether a constituency can be made to ‘swing’. When applied to election results in the Pakistani context, this throws up some very interesting bits of data that emerged when the country last went to the polls.

‘Swing constituencies’ are those that can be won by influencing very small changes in voter preferences. In 2018, there were 81 constituencies where the difference in votes received by the winner and the runner-up was less than 5pc of the total ballots cast

Wafer-thin margins

In the last general elections held in July 2018, the average margin of victory in the 272 constituencies, calculated on the basis of the total valid votes polled (i.e., after subtracting rejected votes from the total votes cast), was 12.6pc. All things considered, that seems like a fairly decent margin overall. However, like all averages, it hides some important nuances.

For example, if we factor in the low voter turnout in the 2018 elections — which was a meagre 51.3pc — the average margin of victory more than halves to 6.1pc of the total registered votes. In simplified terms, if there were 100 voters in each constituency in the 2018 elections, just six more votes would make the difference between victory and defeat for the two top candidates. Interesting, right?

Unpacking the averages uncovers even more interesting bits. The data, for instance, shows there were 81 constituencies among the 272 in 2018 where the difference between the votes received by the winner and the runner-up was less than 5pc of the total valid votes cast, qualifying them to be considered ‘swing’ races. The contests in these constituencies were tighter than the 5pc cut-off initially makes them seem: the average margin of victory in these 81 constituencies was just 2.38pc, and in 23 of those races, the margin was less than wafer-thin at a maximum of 1pc.

Simply put, if only 100 people voted in each of these 81 constituencies, the winner took the seat with just three more votes than the runner-up. And, in the closest races, just one more vote would have been enough to send someone to parliament, and the rest back home.

Bitter rivalries

Of the 81 ‘battleground’ constituencies in the 2018 general elections — i.e., where the margin of victory was less than 5pc — 15 were in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), 45 in Punjab, 15 in Sindh and six in Balochistan. The PTI won most of these constituencies, bagging 38, followed by the PML-N with 16, Independents with eight, PPP-Parliamentarians and MMA with six each, BAP and GDA with two each, and the PML-Q, ANP and JWP with one each.

Among the constituencies the PTI did not win, it was the runner-up in 24, followed by PML-N in 18, Independents in 11, PPP-P in nine, MMA in six, MQM-P in four, BNP and GDA in two each, while an assortment of parties accounted for the remaining five.

Looking at the 23 constituencies where the margin of victory was less than 1pc, the PTI won eight and lost nine; the PML-N won and lost six each; PPP-P won one and lost two. The rest were shared between the other parties.

It gets really interesting if one filters the data to see which of the main parties were fighting against each other in these tight contests. We know the PTI won 38 of the 81 swing constituencies, but who was runner-up in those contests?

It was mainly the PML-N, which came second on 16 such seats, followed by PPP-P in seven, and MQM and MMA in four each. An assortment of other parties and independents accounted for the remaining. Likewise, among the 16 tight races that the PML-N eventually won, it had the PTI chasing close behind in all but two.

The data helps explain, at least in part, why the PML-N and PTI have been the main rivals on Pakistan’s political stage. Since the 2018 elections, both have known they must get ahead mainly by defeating the other. The results tomorrow will show who prepared better.

The geographical context

It is also worth taking a look at the districts where the close contests of 2018 played out, as this may prove useful in identifying where the fights are likely to be fought the hardest in 2024.

PUNJAB: It is impossible to ‘win’ an election without winning Punjab. The province is always the hardest fought, with all parties understanding that whoever takes it will have the pole position to form a government in Islamabad. Given the centrality of Punjab, it is no wonder that most of the closest contests in the 2018 general elections took place there. It can safely be said that Punjab will host most of the tightest races in the latest round as well.

Punjab is also where voter participation is much higher than anywhere else. It had an average turnout of nearly 57pc in the last elections, a full 10 percentage points more than Sindh, and nearly 15 percentage points more than Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Punjab can surely pay dividend to parties that invest time and effort there. By the same yardstick, it can prove to be a tough field to capture.

Of Punjab’s 141 NA seats in the 2018 elections, just about every third constituency was won or lost with a margin of less than 5pc. Major urban centres were where most of the closest battles were fought, with Faisalabad accounting for five such contests; Multan, four; and Lahore, Bahawalpur, Sargodha and Khanewal accounting for three each. Muzaffargarh, Rawalpindi, Nankana Sahib, Kasur, Sialkot, Lodhran and Layyah also saw some action, with each district throwing up two contests apiece where there was not much separating the victor and the vanquished.

The tussle, again, was mainly between the PML-N and PTI. The latter won 24 of the total 45 such constituencies. The PML-N won 15. The PTI came in second in 17 if these contests, while the PML-N was runner-up in 16.

Narrowing it down further, among the 45 constituencies, 22 were the closest, with the margin of victory ranging from 0.03pc to 2.1pc. The PTI came out on top in 10 of these seats, and the PML-N won nine. Among the constituencies they did not win, both the PTI and PML-N were in the second place on nine seats each.

After the recent delimitations, 19 of these 45 constituencies have been significantly altered, so it is difficult to say whether the voting trends will be similar in the corresponding new constituencies. Among these 19 constituencies, 10 were won by the proverbial hair’s breadth, with the margin ranging between 0.03-2.1pc. However, analysts may want to keep an eye on the 26 remaining constituencies that stand unaltered or have been modified only slightly.

KP: In KP, disregarding the merged seats of erstwhile Fata, there were 10 constituencies where the margin of victory in 2018 was below 5pc. These were: Upper Dir, Shangla, Kohistan, Mansehra-I, Mardan-II, Mardan-III, Bannu, Lakki Marwat, Mohmand and North Waziristan.

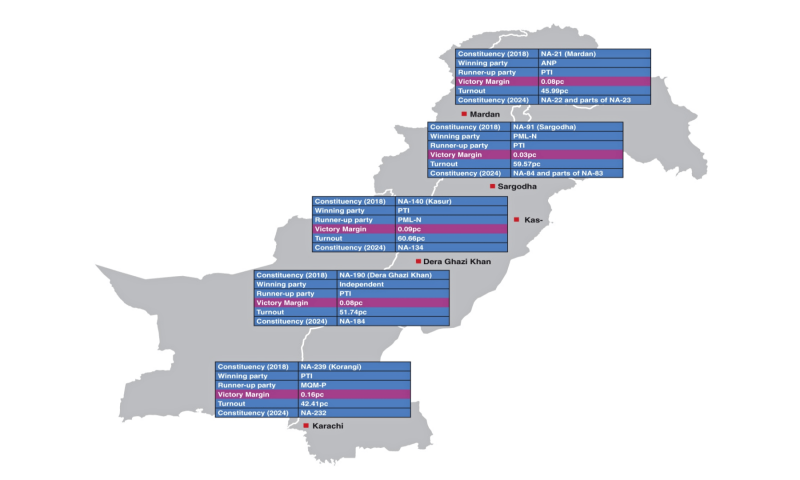

Among these, the tightest races in 2018 were between the ANP and PTI in NA-21 Mardan-II, which the ANP won with a 0.08pc margin; the race between an Independent candidate and PML-N for NA-13 Mansehra-I, which was won by the former with a 0.73pc margin; and the contest for NA-22 Mardan-III between the PTI and MMA, which was won by the former with a margin of 1.05pc.

For the 2024 general elections, NA-21 and NA-22 have both been significantly altered by delimitation: NA-21 has been split between the new NA-22 and NA-23, while NA-22 has been split between the new NA-23 and NA-21. Besides, NA-13, which is now numbered NA-14, has seen some minor changes. This means three of the toughest KP constituencies in 2018 have undergone major alteration, while the rest are more or less the same, or have been altered slightly.

BALOCHISTAN: In Balochistan, six constituencies were closely fought; Loralai-Musakhail-Ziarat-Dukki-Harnai, Dera Bugti-Kohlu-Sibi-Lehri, Quetta-II, Mastung-Kalat-Shaheed Sikandarabad, Panjgur-Washuk-Awaran, and Lasbela-Gwadar.

Of these, NA-270 Panjgur, NA-259 Dera Bugti and NA-267 Mastung were the most closely fought, featuring contests, respectively, between BAP and BNP-A, JWP and an Independent, and MMA and BNP. The BAP, JWP and MMA emerged as victors with margins of 0.81pc, 0.82pc and 0.85pc.

Of the three, only NA-267 Mastung (now NA-261) has remained unchanged. The others have been significantly redrawn, with the old NA-270 and NA-259 now split between three and two new constituencies, respectively.

SINDH: Of Sindh’s 15 closely fought races, seven were in or around Karachi. These included the fights for Korangi-I and III, Malir-II and Karachi West-I, II, III and V. The PTI was victorious on six of these seats, with margins ranging from 0.16pc to 4.54pc.

Four of these constituencies have been majorly redrawn for the 2024 elections; NA-237 Malir-II, which is now split between the new NA-231 and NA-235; NA-248 Karachi West-I, which now roughly corresponds with NA-243; and NA-250 Karachi West-III and NA-252 Karachi West-V, of which NA-250 now roughly corresponds to NA-242, while NA-252 has been split between NA-244 and NA-255.

Elsewhere in Sindh, the close fights were in Jacobabad, Shikarpur-II, Ghotki-I, Naushahro Feroze-II, Sanghar-I, Mirpurkhas-I, Tharparkar-I and Badin-II, of which four were contests between the PPP and GDA, with each winning two (PPP-P in Naushahro Feroze-II and Sanghar-I; GDA in Shikarpur-II and Badin-II).

The PTI and PPP-P were also head-to-head in two of these constituencies, Jacobabad and Tharparkar, each winning one (PTI in Jacobabad, and PPP in Tharparkar). For the elections tomorrow, the relevant constituencies in Sanghar and Shikarpur have been significantly altered.

Cracking and packing, explained

The constituencies corresponding to the ones which saw close contests in the 2018 general election will be interesting to watch, inasmuch as they will show how successful parties were in flipping past defeats into victory. ‘Swinging’ a tight constituency does not always require hard work. There are other, more devious means to turn defeat into victory. Those who know how to work the system use them without shame.

One of the most devious and least understood among these underhanded tactics is to attempt to influence the delimitation process. For example, a party which may have lost a constituency in the last election by a tiny margin can, when the constituency is being redrawn, have more of its voters moved in and its opponents’ voters moved out.

This is referred to as ‘cracking’ and ‘packing’: i.e., you crack up your opponent’s vote bank and distribute it between neighbouring constituencies and/or pack more of your own voters from neighbouring constituencies into your own.

This is not to suggest any gerrymandering has indeed taken place in the recent delimitation. After all, considering the major changes in population between the 2017 census and the one notified in August 2023, significant alterations to constituency boundaries were necessary in any case.

However, with 98 of the 272 constituencies from the 2018 elections significantly redrawn by the ECP for the upcoming polls, some suspicion about how fairly the process was completed ought to be expected, especially with some established analysts stating on record that certain parties seem to have been favoured in certain places. It is unfortunate that this matter has not been raised much publicly since the Supreme Court earlier stayed the challenges against delimitations till after the general elections are over.

Other devious means used to sway results in tight races include measures to discourage rivals’ voters from casting their votes. This can take many forms, ranging from tactics to discourage citizens from leaving their homes, to preventing parties from transporting candidates to polling stations, to disrupting or slowing down the voting process so that the voters are forced to turn back or wait for extended periods.

It does not end here, though. Once voting is completed, the contesting candidates and their teams need to be on top of their game. Polling agents have to protect their party’s votes during the counting process and make sure each vote gets counted by the presiding officer.

Then, they must ensure that the copy of the vote tally they are issued matches with the final count announced by the Election Commission, lest they need to challenge the results or point out any irregularity in the counting process. If the party ahead even slightly drops its guard, the next in line is waiting to take advantage. At the end come the recounts and petitions.

The toughest victories are clearly not easy to keep, and, as discussed, victory is not the only outcome of a successful campaign. Sometimes the slightest complacency can make one lose the game. With D-Day tomorrow, the line between the victor and the vanquished will be clearer sooner rather than later.

Published in Dawn, February 7th, 2024

To find your constituency and location of your polling booth, SMS your NIC number (no spaces) to 8300. Once you know your constituency, visit the ECP website here for candidates.