From poor female employment numbers to a growing housing crisis, Karachi Census 2023 presents an accurate image of issues that need to be addressed in the city.

“Statistics are used much like a drunk uses a lamppost: for support not illumination.” — Vin Scully, American Sports Commentator

Karachi’s Census 2023 results have lifted the veil on the city’s explosive growth, painting a portrait of a population in flux and a metropolis grappling with the sheer weight of its own sprawl. This data, a treasure trove for urban planners and policymakers, lays bare the challenges of managing a city that seems to defy all predictions — its sprawling tentacles reaching out with an insatiable appetite for space and resources.

The census data, a snapshot frozen in time, captures Karachi at a moment of transformation. As the city’s skyline pierces the clouds and its arteries pulse with the rhythm of millions, the census data provides a roadmap for navigating the complexities of managing this burgeoning metropolis. Let us delve into the salient findings of the census 2023…

THE STORY IN NUMBERS

With a total population of 20,357,474, a striking disparity emerges in the distribution of Karachi’s population, with District Central and District East towering over the rest, each harbouring nearly four million residents. In stark contrast, Kemari district, with just over two million residents, lags significantly behind, suggesting a different trajectory of development, potentially marked by limited resources, infrastructure gaps or distinct patterns of land use.

While the mountain of data and numbers presented under the findings of the Karachi Census 2023 may seem daunting and impenetrable, they present policymakers and citizens alike with an accurate image of the issues that need to be addressed in the city. From poor female employment numbers to a growing housing crisis, the data gives us a glimpse into the work that needs to be done…

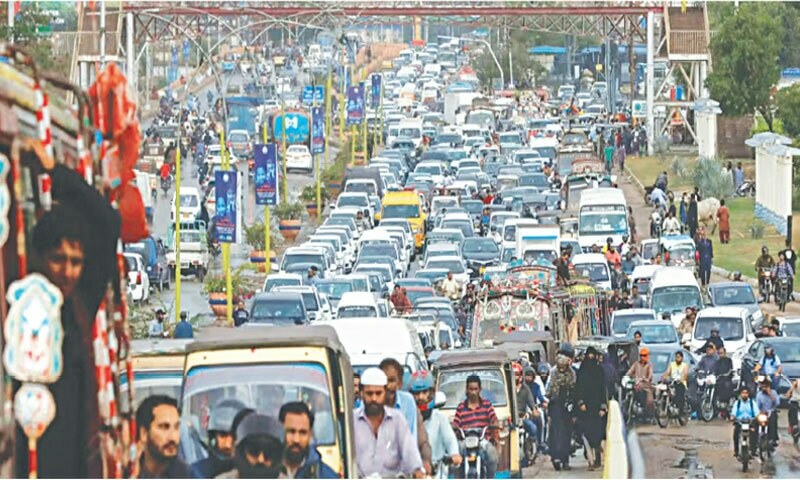

This uneven distribution of population across Karachi’s seven districts has far-reaching implications for urban planning, resource allocation and service delivery. Overcrowding in densely populated areas such as District Central and District East strains existing infrastructure and exacerbates social challenges, while less populated districts such as Kemari might require targeted investments to stimulate growth and improve living standards.

Table 2 showcases the subtle yet significant shifts in the percentage share of each district within the city’s burgeoning population and a raw, numerical testament to this change. District East emerges as the undisputed champion, boasting the most substantial population influx between 2017 and 2023.

Districts Central and West also experienced significant growth, mirroring the city’s relentless march towards urbanisation. In contrast, Kemari district witnessed a more subdued growth trajectory, hinting at potential economic and demographic shifts within this specific area. These figures, coupled with the subtle shifts in district-wise population shares, reveal a city in constant flux, with residents gravitating towards Central and East districts, while others experience a relative slowdown in growth.

Karachi’s population growth, as depicted in Graph A, reveals a fluctuating trend over seven decades. From 1951 to 2023, the city’s growth rate has charted a downward course, albeit with minor elevations. The most significant surge occurred between 1951 and 1961, with a dramatic 6.18 percent increase, likely fuelled by post-Partition migration.

Subsequent decades witnessed a gradual decline, interrupted briefly by a slight rise in the 1970s. The most recent figures, however, indicate a moderate growth rate of 3.62 percent between 2017 and 2023.

UNEVEN GROUND

Women, numbering exactly 9,567,463, make up 47 percent of Karachi’s sprawling populace — a significant demographic force whose stories are often untold. In 1951, women constituted a mere 42.68 percent of the city’s population. Fast forward to 2023, and their presence has surged to approximately 47 percent, a testament to the changing tides of gender dynamics.

A glance at the numbers reveals intriguing patterns. While seemingly spread relatively evenly across districts, subtle percentage differences highlight underlying socio-economic dynamics. Areas such as districts Central and East show slightly higher percentages of female population (around 19.15 percent of the total female population of Karachi Division), hinting at potential in-migration for work or family ties. Districts such as Malir, traditionally dominated by more ethnically diverse communities, also demonstrate substantial female representation, exceeding 11.88 percent of the total female population of Karachi Division.

However, the devil lies in the details. While overall female numbers are significant, the percentage distribution within each district reveals a nuanced story. Do these numbers translate to proportional access to resources, healthcare, education and job opportunities? The data doesn’t explicitly tell us this, but it prompts crucial questions.

The transgender numbers, while significantly smaller, also deserve attention. Numbering 2,622 in total, their representation across districts is uneven, with Korangi notably showing a higher concentration. This raises questions about social acceptance and support structures for this marginalised community within specific localities.

A CITY OF MIGRANTS

Karachi, a city forged by the several waves of migration, has witnessed a remarkable demographic shift. The city’s urban transformation has been nothing short of dramatic. In 1941, a rural landscape dominated, with 45 percent of the city classified as rural. However, the influx of migrants from India in the aftermath of Partition triggered a rapid urbanisation.

Within a decade, Karachi had metamorphosed into a predominantly urban landscape, with a staggering 95 percent of its area classified as urban. The wave of migration in the 1970s, after the separation of East Pakistan, further solidified this trend, pushing the urban footprint to a remarkable 97 percent in 1972.

On the other hand, the internal migrants, driven by cultural proximity, livelihood opportunities and the affordability of land, gravitated towards the city’s remaining rural pockets — such as District Malir and District West — offering a glimpse into the complex interplay of urban growth, rural realities, and political manifestations and ethnic consolidation of neighbourhoods.

Karachi’s rapid urbanisation, fuelled by migration, created both opportunities and challenges. While the city became a hub of economic activity and cultural diversity, it also grappled with the consolidation of neighbourhoods on an ethnic basis, the strain on resources and infrastructure, issues of inequality, the exacerbation of a search for the city’s ‘identity’ and complex political dynamics. All this is reflected in the multitude of languages spoken in the city.

THE SHIFTING TIDES OF LANGUAGE

Karachi, a city renowned for its cultural tapestry, continues to evolve. The census data reveals a fascinating shift in the city’s linguistic landscape. While Urdu remains the dominant language, spoken by 50.67 percent of the population, Pashto and Sindhi are making significant gains.

Compared to 1998, when Urdu was spoken by 48.52 percent of the population, its dominance has slightly increased. District Central remains an Urdu stronghold, with 80 percent of residents speaking it as their first language. However, in Malir, Urdu speakers constitute only 16 percent of the population.

Pashto has emerged as the second-most spoken language, with 13.52 percent of Karachiites identifying it as their mother tongue. Kemari district stands out as a hub for Pashto speakers, with 33 out of every 100 residents speaking it as their primary language.

The Sindhi-speaking population has witnessed a substantial surge. In 1998, only 7.62 percent of Karachiites identified Sindhi as their mother tongue. This figure has risen to 11.2 percent in 2023. District Malir boasts the highest concentration of Sindhi speakers, with 35 percent of the population, while District Central has a mere two percent.

Conversely, the Punjabi-speaking population has seen a decline. In 1998, 14.94 percent of Karachiites spoke Punjabi as their first language. This figure has dropped to 8.08 percent in 2023. Kemari district hosts the largest concentration of Punjabi speakers (11 percent), while District Central has only four percent.

Kemari and Malir districts stand out for their linguistic diversity. Kemari has a significant Hindko-speaking population (eight percent), alongside a substantial Pashto-speaking community. Malir has 16 percent Urdu and 18 percent Pashto speakers. This linguistic diversity suggests that these districts may see a rise in political leadership from Pashto and Sindhi-speaking communities in the future.

Karachi’s evolving language map isn’t merely a matter of demographics, it’s a harbinger of shifting power dynamics. The rise of certain languages will likely reshape influence within local governance and redefine the city’s leadership. One can expect to see a surge in efforts to preserve and promote diverse cultural interests, vying for space and recognition in public life and the economic sphere. This linguistic and cultural renaissance will likely become a defining characteristic of Karachi in the coming years.

HOUSING THE HOMELESS

Amidst the bustling metropolis of Karachi, home to a staggering 20.3 million people living in 3.439 million housing units, lies a stark reality: a significant portion of the population remains without a permanent roof over their heads.

The census data reveals a city sharply divided: 99.6 percent of population is living in what the census classified as a “regular household”, comprising families residing in traditional homes. However, the remaining 0.34 percent — a stark reminder of the city’s deep-rooted inequalities — encompasses both institutional households (0.19 percent) and the homeless (0.15 percent).

The burden of homelessness falls disproportionately on certain areas of the city. District South and District Central, known for their dense urban fabric, together account for a staggering 55.02 percent of all 29,806 homeless in Karachi. This is particularly alarming considering that District South, despite housing only 11.42 percent of the city’s regular households, bears the brunt of homelessness, with a staggering 28.21 percent of all homeless individuals residing within its boundaries.

The census data, however, lacks the granularity needed to understand the nuances of homelessness. A more detailed typology of homelessness is crucial for developing effective and targeted housing policies.

RELIGIOUS DEMOGRAPHICS

In the Census 2023, Islam reigns supreme as the dominant religion, constituting a commanding 96.52 percent of the city’s population. Christianity, with a 2.14 percent share, emerges as the largest religious minority. While a slight decline from the 1998 Census (2.42 percent), Christians remain a significant presence in the city.

Hinduism, on the other hand, is witnessing a steady rise. From a modest 0.78 percent in 1981, the Hindu population grew to 0.83 percent in 1998 and now stands at a notable 1.17 percent in 2023. The Parsi/Zoroastrian community, once a prominent part of Karachi’s history, is facing a precipitous decline. A mere 0.20 percent of the population in 1981, their numbers dwindled to 0.07 percent in 1998 and now stand at a dismal 0.01 percent in 2023.

District South boasts the highest concentration of religious minorities. While Muslims constitute a majority (93.85 percent), a significant Hindu population (4.14 percent) resides alongside small Sikh (0.03 percent) and Parsi (0.04 percent) communities. District West also harbours small Sikh (0.02 percent) and Parsi (0.01 percent) populations. Korangi District has a significant Christian presence (3.42 percent), while Malir is home to a small Scheduled Caste Hindu population (0.09 percent).

Religious demographics can have implications for political representation and advocacy. As minority groups grow or shrink, their ability to effectively voice their concerns and influence policy decisions can also change. The data underscores the need for inclusive political systems that ensure the voices of all religious communities are heard and considered.

TYING THE KNOT IN KARACHI

Karachi’s marriage patterns reveal a fascinating story of shifting tides. From 1951 to 1972, a gradual decline in marriage rates was observed. However, a surprising reversal occurred, with a slight uptick in 1981 and a more pronounced increase in 2023. Throughout this period, a significant gender disparity persisted, with women consistently exhibiting higher marriage rates than men. This gap, which widened between 1951 and 1998, has shown signs of narrowing in recent years.

A closer look at the district-level data reveals intriguing variations. While Central and East districts exhibit similar patterns with high marriage rates, District West stands out with the highest percentage of married residents. In contrast, Kemari and Korangi show a moderate level of marriage alongside a higher proportion of never-married individuals. Malir, on the other hand, boasts the highest percentage of married residents, suggesting unique social and demographic dynamics within each district.

To gain a deeper understanding of the findings, further research is imperative. This includes analysing age-specific marriage rates, examining the intricate interplay between marriage rates and socio-economic indicators, and conducting in-depth studies to understand the cultural and social factors influencing marital decisions within different districts.

THE CLIMB TOWARDS KNOWLEDGE

Graph E paints a picture of Karachi’s journey towards literacy, a story marked by progress, setbacks and the enduring pursuit of knowledge. One striking aspect is the persistent gap between male and female literacy rates.

In 1951, just 42.87 percent of the population was literate. By 2023, this figure had more than doubled to 70.65 percent. In 1951, a mere 39.02 percent of women could read and write, compared to 45.50 percent of men. This disparity persisted throughout the decades, though the gap narrowed somewhat. By 2023, women’s literacy stood at 68.03 percent, still trailing behind the 72.09 percent achieved by men.

Despite the challenges, the overall trend is one of progress. The graph also offers a glimpse into the past. The dip in literacy rates between 1961 and 1972 serves as a reminder that progress is not always linear.

The census data reveals a telling disparity between its districts. District Central leads the pack with a total literacy rate of 78.60 percent, closely mirrored by its male literacy at 78.68 percent and a slightly lower female literacy of 78.52 percent. District East follows a similar pattern, hovering around 75-76 percent for both total and gender-specific literacy. District South mirrors this trend, with an overall rate of 75 percent, though a noticeable gap emerges between male (76 percent) and female (72 percent) literacy.

The data highlights a significant drop in literacy rates in Kemari, registering only 58 percent overall, with male literacy at 62 percent and female literacy lagging significantly at 53 percent. West (63 percent) and Malir (59 percent) districts also exhibit relatively lower literacy rates compared to the leading districts.

KARACHI’S WORKFORCE

According to the census 2023, the overall employment rate stands at 39.10 percent, which is better than 1981 (33.43 percent) and 1998 (27.58 percent). Despite such gains, Karachi’s women are fighting for a place in the workforce, and the numbers reveal a long and arduous climb. Decades of data show a stark disparity in employment rates, with women consistently lagging behind their male counterparts.

In 1951, a meagre 3.34 percent of women were employed, compared to a significantly higher 78.38 percent of men. While some progress has been made over the years, the gender gap persists. By 2023, women’s employment rose to a still-low 11.04 percent, while male employment decreased to 63.65 percent. Although the gap has narrowed, women’s participation in the workforce remains far below parity.

A GRIM REALITY FOR THE DISABLED

The data lays bare a stark truth about disability in Karachi. A staggering 11.52 percent of the total disabled population of 581,353 (2.55 percent) grapples with a physical disability. In 1998, the total number of disabled persons in Karachi was 423,133, which was 4.60 percent of the total population at the time. This increase (158,220 persons) in absolute numbers is particularly alarming for men, with 2.58 percent facing challenges, compared to 2.51 percent for women. The population with functional limitation is 11.52 percent of the total population of Karachi Division, with males making up 11.68 percent and females constituting 11.35 percent.

The data reveals a spectrum of struggles. Visual impairments impact 2.18 percent of the population, while hearing difficulties affect 2.51 percent. Mobility challenges, including walking and climbing, are prevalent, affecting 3.51 percent of the population. Communication and memorisation issues also pose significant hurdles for 1.15 percent and 1.72 percent, respectively.

The data underscores the necessity for inclusive policies, accessible infrastructure and targeted interventions to ensure that everyone, regardless of their abilities, can thrive.

THE ENERGY DIVIDE

While a vast majority (98.27 percent) of urban households rely on electricity, rural areas lag behind, with only 85.34 percent accessing this essential service. Solar panels are emerging as a viable alternative in rural areas, powering 8.27 percent of households, while other sources, such as generators or traditional fuels, account for the remaining 6.39 percent.

Graph G reveals a stark contrast in fuel usage between rural and urban Pakistan. While natural gas dominates in urban areas, powering 91.63 percent of households, its reach in rural areas is significantly lower at 61.27 percent. This gap is filled by more traditional fuels such as firewood (28.46 percent in rural areas) and liquefied petroleum gas or LPG/liquefied natural gas or LNG (8.83 percent).

WHY THE DATA DEMANDS ACTION

These numbers only scratch the surface of Karachi’s complex reality. Employment rates, the ebb and flow of inter-district migration, levels of educational attainment, the diverse landscape of housing structures and water sources are crucial elements that remain largely unexplored here. Limited space and the need for clearer definitions from census authorities prevent a deeper dive into these vital statistics.

The census data reveals stark disparities across districts, with population concentrated in the Central and East districts straining resources and infrastructure, while Kemari lags behind in development. This uneven growth necessitates targeted interventions to ensure equitable access to services and opportunities for all residents.

The persistent gender gap, with women comprising just 47 percent of the population and facing employment rates far below parity (11.04 percent, as opposed to 63.65 percent for men), demands urgent action to address systemic inequalities and empower women. The city’s evolving linguistic landscape, with the rise of Pashto and Sindhi alongside Urdu, also requires careful attention to ensure social cohesion and political representation for all groups.

The data also exposes a troubling housing crisis, with thousands of people being homeless despite the availability of millions of homes, highlighting the urgent need for affordable housing solutions, particularly in districts such as South and Central.

Furthermore, disparities in access to basic necessities such as energy, with rural areas lagging significantly behind urban centres, require immediate investment in infrastructure and sustainable energy solutions. The data on disability underscores the need for inclusive policies and accessible infrastructure to ensure equal participation for all citizens.

Finally, while Karachi has made strides in literacy, with the rate reaching 70.65 percent, the gender gap persists, emphasising the need for continued investment in education, particularly for women and girls.

If current trends continue, Karachi in 2033 could be a city even more divided, with widening gaps in income, access and opportunity. The challenges are immense, but the data provides a crucial roadmap for policymakers and urban planners. The next few years will be critical in shaping the future of this vibrant yet fragile metropolis.

Mansoor Raza is a Karachi-based academic and a board member of the Urban Resource Centre. He can be reached at mansooraza@gmail.com

Umer Ahmed Khan is an undergraduate student at NED University in the Department of Architecture and Planning (Development Studies Programme)

Header image: Congested road traffic in Karachi during the evening rush hour: the uneven distribution of population across Karachi’s seven districts has far-reaching implications for urban planning, resource allocation and service delivery | Reuters

Published in Dawn, EOS, February 9th, 2025

- Desk Reporthttps://foresightmags.com/author/admin/