Indonesian authorities were counting votes cast on Wednesday in the world’s biggest single-day election, headlined by the race to succeed President Joko Widodo, whose influence could determine who takes the country’s helm.

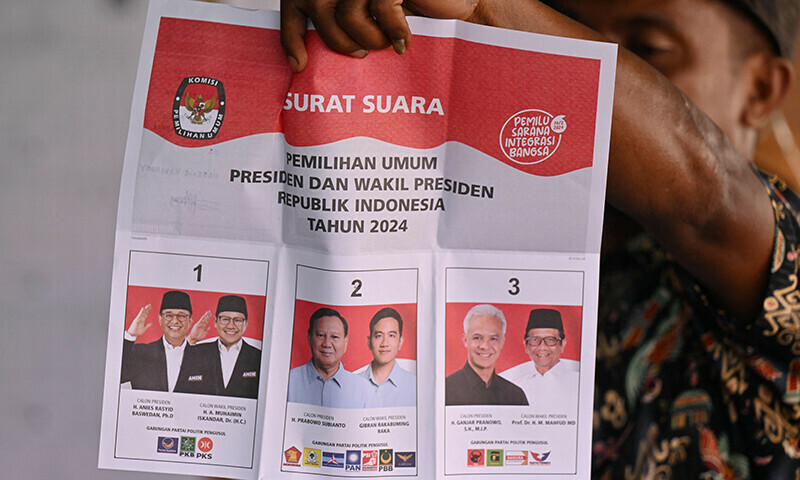

The race to replace Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi, pits two former governors, Ganjar Pranowo and Anies Baswedan, against controversial frontrunner Prabowo Subianto, the defence minister and a former special forces commander feared in the 1990s as a top lieutenant of Indonesia’s late strongman ruler Suharto.

Initial indications of the result are expected to emerge later on Wednesday, based on independent pollsters’ ‘quick counts’ of publicly counted votes from a sampling of stations across the country. In previous elections, the unofficial counts have proven to be accurate.

Election laws prohibit publication of quick counts before 0800 GMT. The General Election Commission is expected to announce official results by March 20 at the latest.

All eyes are on the presidential race and the fate of the Jokowi’s plans to establish the country as an electric vehicle hub and extend a massive infrastructure push, including a multi-billion dollar plan to move the capital city.

Two surveys last week projected Prabowo, who has promised to continue Jokowi’s programmes, will win the majority of votes and avoid a second round.

Those surveys showed Prabowo with 51.8 per cent and 51.9pc support, with Anies and Ganjar 27 and 31 points adrift, respectively. To win outright, a candidate needs over 50pc of votes and to secure 20pc of the ballot in half of the country’s provinces.

Novan Maradona, 42, an entrepreneur, said after voting in central Jakarta he wanted a candidate who would continue policies currently in place.

“If we start over from zero, it will take time,” he said.

Indonesia has three time zones and most polling stations across the country had closed by 0600 GMT.

Voting got off to a slow start in Jakarta, with thunderstorms causing flooding in parts of the capital. About 70 polling stations were affected, but it was not clear whether any delays would impact turnout. Turnout in past elections has been about 75pc.

Some polling stations in Central Java and Bali were decked out in pink and white Valentine’s Day decorations, while others in West Java province handed out fruit to waiting voters.

Call for clean election

Undecided voters will be critical to former Jakarta governor Anies and ex-Central Java governor Ganjar, to try to force a runoff in June between the top two finishers.

“I want to underline that we want honest and fair elections so that it becomes peaceful,” Anies said at a polling station.

Deadly riots broke out after the 2019 election, when Prabowo, who has run previously for president, had initially contested Jokowi’s victory.

Some 200,000 security personnel are on guard.

“So far, the situation is safe, under control,” said National Police Chief Listyo Sigit Prabowo. “We will keep monitoring until the voting process is done and we are prepared for any impact after the voting.”

Anies has campaigned on promises of change and preventing a backsliding in the democratic reforms achieved in the 25 years since the end of Suharto’s authoritarian, kleptocratic rule.

Ganjar hails from the Indonesia Democratic Party of Struggle, of which Jokowi is ostensibly a member, and has campaigned largely on continuing the president’s policies, but crucially lacks his endorsement.

Before voting, he also called for a clean election so that candidates could accept the result.

Prabowo said on Wednesday he hoped the “voting process goes well”.

The defence minister is contesting his third election after twice losing to Jokowi, who is tacitly backing his former rival, seen as a continuity candidate to preserve his legacy, including a role for his son as Prabowo’s running mate.

During his decade in office, Jokowi pushed to attract investment, introducing laws that slashed red tape and streamlined business rules. His administration’s efforts to contain inflation have benefited millions and per capita income has risen, according to World Bank data.

Prabowo rebrand

The 72-year-old Prabowo has pledged to continue Jokowi’s policies and at the same time transformed his image from a fiery-tempered nationalist to a cuddly grandfather figure with awkward dance moves.

Prabowo’s more gentle characterisation, played out largely on short video app TikTok, has endeared him to voters under 40, who make up more than half of the 204.8 million electorate.

A 25-year-old student Keko Iyeres said he wanted to see improved education and justice.

“I like Prabowo because he is aggressive but can also be gentle. We need a leader like that. And I see that Jokowi also supports him.”

But Jokowi’s intimated support for Prabowo, plus allegations he interfered in a court ruling to allow his son to contest the vice presidency, have prompted criticism that unlike previous presidents he is not staying neutral over his succession.

Jokowi’s loyalists have rejected that and it is unclear if the allegations will impact Prabowo.

Asked about allegations of foul play, including in a documentary called “Dirty Vote” that went viral on social media this week, Jokowi said there were mechanisms to report issues.

“If there is cheating on the ground, that can be reported to Bawaslu (the election watchdog) and then … a petition can be brought to the Constitutional Court,” he said.