Professional, responsive and selfless media and civil society, built on informed public trust, form a unified front against the oppression of the state apparatus and the powerful elite. In settings with vibrant media and civil society, citizens find genuine hope and justice. However, civil society and media individuals – driven by selfishness, greed, power hunger and popularity-seeking tendencies – orchestrate against and put citizens’ lives under a multitude of systematically enforced chains. Kashmore, a district in northeastern Sindh, exemplifies a classic case study of life buried under the crisscrossing shackles of modern slavery. Local media and the so-called civil society have a considerable stake and say in this regard.

Although multiple overlapping nexuses, including feudal-political-tribal-bandit, political-bureaucratic, and feudal-bandit networks operate collaboratively with overt state support in the district, the nexus evolved by civil society and bureaucracy adds to the strength of systematic slavery. Cloaked as saviours, the two have made and continue to make utmost efforts to rob citizens of the prospects of peace and prosperity. However, it is essential to specifically define the elements of the civil society-bureaucratic nexus in the district and its modus operandi.

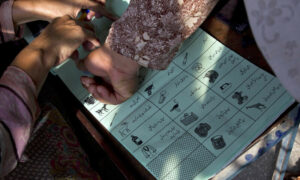

Civil society in the district is mainly comprised of local reporters from mainstream media (who mistakenly identify themselves as journalists), clergy, influential pirs, prominent religio-political and national parties, tribal lords, attention-seekers and self-styled social activists. Most of them, with their misguided public appeal, forged mutually beneficial links – or, more aptly, a nexus – with bureaucrats (both civil and police) and a parasitic one with the public. Inspired by the bureaucratic and political elite, the district’s civil society has positioned itself as the public’s saviour, garnering trust from citizens – albeit a misguided one, especially among the socio-economically and intellectually disadvantaged. This misguided public trust is what it uses for forging connections with sponsored local bureaucracy. These connections encourage civil society activists, regardless of affiliation, to cordially receive newly posted bureaucrats and garland them. This affords both parties almost absolute impunity, enabling them to become apathetic to the public and act at their will, contrary to the public good.

Similar to the sponsorship of feudal lords in peripheral areas, many civil society members abet, if not tame or sponsor, outlaws in major cities like Kashmore, Kandh Kot and Tangwani by shielding them from accountability for their criminal activities. For this purpose, they leverage their connections and stakes among officials. In return, they remain largely inactive on major issues affecting the public, including street crimes. However, to balance their ill-gotten public support and connections with local bureaucracy, among others, they stage ritualistic and half-hearted actions. These two-faced policies perpetuate their influence, leaving citizens to perpetually struggle with issues in the eternal false hope of their resolution.

Drawing inspiration from other nexuses and emboldened by their connections, civil society activists have emerged as significant beneficiaries of citizens’ agonies and the prevailing lawlessness. Most of them play on both sides, simultaneously pretending to stand with both the aggrieved and the aggressor. Courtesy their double-standard role, they reap benefits, apart from ill-founded public appeal, by exploiting the public cause and currying favour with local influentials. The tribalistic demography, feudalistic influence and LAE’s apathy and politicisation have transformed the district into a hotbed of patronised outlaws. These outlaws, compounded by multiple and overlapping nexuses, have dashed citizens’ aspirations for peace and prosperity.

For the sake of citizens’ well-being, it is imperative that governing authorities, state functionaries, PEMRA, mainstream media owners and senior leaders of nationalistic and religio-political parties ensure that their delegated powers and affiliations are not misused or exploited in ways that exacerbate public miseries in the district.