Pildat president says electables are politicians who can be elected without the support of a political party because of their cultural or religious clout.

With the Feb 8 general elections fast approaching, major political parties have scrambled to woo electables across Pakistan, trying to out-manoeuvre each other in a bid to boost their prospects post-Feb 8.

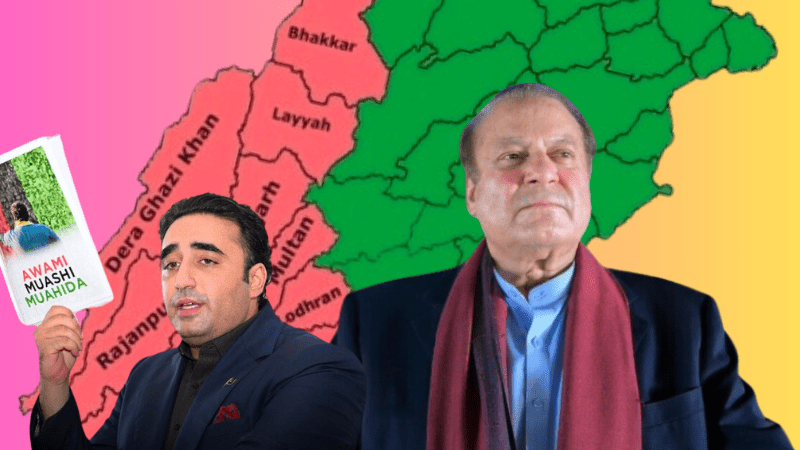

Over the past few months, the PML-N and PPP appear to have made decent inroads in Balochistan and south Punjab, which are ground zero for all electable contests ahead of a major election.

Former prime minister Nawaz Sharif, whose PML-N now carries the tag of ‘king’s party’, visited Balochistan in November and managed to add over two dozen electables to his arsenal. The party also managed to secure a foothold in South Punjab by relying on electables.

Following in the footsteps of the Sharifs, the father-son duo Asif Ali Zardari and Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari also kicked off the PPP’s election campaign in Balochistan in a bid to make inroads in the province to some degree of success. The PPP also upped its presence in Punjab, intending to lure electables to improve its position in a province otherwise dominated by PTI and PML-N supporters.

For the PTI, which is facing myriad challenges in the upcoming polls, electables are off the list.

It must be noted that electables played a significant role in forming the Imran Khan-led government in 2018. However, it looks like the PTI — which has fallen from grace in spectacular fashion — has failed to get its hands on any this time around.

Who are electables?

The Oxford Learner’s Dictionary defines an electable as: “(of a politician or political party) having the qualities that make it likely or possible that they will win in an election.”

While the term electables may be a recent coinage, the phenomenon has a long history tracing back to the colonial days when the British used the intervention of the rural elite for an effective rule.

Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (Pildat) President Ahmed Bilal Mehboob tells Dawn.com that electables are political leaders who can be elected without the support of a political party because of their cultural or religious clout.

“These people usually hail from places where there is large land ownership, for example south Punjab and Sindh,” he says, explaining that land workers are dependent on such leaders and become “hostage voters”.

Electables, Mehboob continued, are not bound by party discipline and can easily be made to join any political party — usually at the “whims and wishes of the establishment”.

According to a report published in Republic Policy in November 2023, the origins of electables can be traced back to the 1985 non-party elections held during the regime of military dictator General Ziaul Haq.

“In a bid to prolong his authoritarian grip, Zia sought to empower local strongmen, allowing them to contest elections without formal party ties. This resulted in a surge of electables, primarily drawn from the ranks of landlords, tribal chiefs, and influential figures, who capitalised on their entrenched power bases to secure victories,” the report said.

Similarly, the late Gen Pervez Musharraf carved out the Pakistan Muslim League-Quaid (PML-Q) from the PML-N at the turn of the century.

Over the years, electables have become a crucial pillar in the political arena as their influence extends beyond constituencies, over districts and sometimes even cities.

For instance, former foreign minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi and his family enjoy unwavering support in Multan. He had joined the PML-N before the 1988 general election. Just before the 1993 general election, he joined the PPP after Nawaz Sharif declined to make him PML-N’s candidate for a National Assembly.

In 2011, he ended his 18 year-long association with the PPP, months after being stripped of the portfolio of foreign minister amid a controversy regarding diplomatic immunity for a CIA contractor who killed two Pakistanis in Lahore in January. That same year, he then joined Imran Khan’s PTI, which he is still a part of.

Can they make or break polls?

But do these electables play such an important role in elections that an entire article is dedicated to them? Unfortunately, yes.

Usually, the party that emerges victorious in the general elections as well as the runner-up do not have much difference in the number of seats they have clinched, Pildat’s Mehboob explained. The gap usually amounts to five to 10 seats.

“Any party that succeeds in wooing electables and bringing them to its side is the winner. This way, electables can make or break polls,” he says.

PTI founder Imran Khan formed his government in 2018 in a similar fashion. Despite enjoying massive popularity, his party was only able to secure a majority in the National Assembly after electables joined the PTI ahead of the polls.

More than 60 electables from Punjab, especially those who had belonged to the PML-N and PPP, had joined the PTI ahead of the 2018 general elections. The party of the Sharifs had alleged that the establishment had compelled these leaders to ditch the PML-N so that Imran could be conveniently “brought to power”.

But with 172 seats in a 342-member house, the PTI had gained only a simple majority. Some nudging here and there could topple his government like a house of cards, which is exactly what happened in the run-up to his ouster on April 9, 2022.

Further, after the events of May 9 — when violent protests erupted across the country following Imran’s arrest outside the premises of the Islamabad High Court — analysts say political engineering was deployed to force or tempt away those political leaders and electables who were earlier sent to the PTI.

But PTI is not the only major political party to have adopted the strategy. The PML-N has also shown a preference for electables in a number of instances, including the upcoming polls.

The fault in our stars

Dawn’s Islamabad bureau chief Journalist Amir Wasim says that the number of electables has shrunk over time. “You will find more of these people in rural areas as compared to urban areas.”

“But these people have always played an important role in elections,” he says, adding that these political leaders do not have ideologies. Instead, they only possess constituencies and join political parties on their own terms and conditions.

Basically, with the right number of electables on its side, a political party can easily win the numbers game.

However, Pildat’s Mehboob says that the establishment has a hand in nudging electables in a particular direction. In 2018, it appears that it was Imran Khan. Nearly six years later, it seems as if the stars are in the favour of Nawaz.

But electables are like coins — they have two sides. Also termed turncoats, the role of electables has led to the destructive practice of floor crossing and horse-trading.

Former lawmakers including Noor Alam Khan, Raja Riaz, Ramesh Kumar and Basit Bukhari were part of PPP and PML-N before they switched to the PTI and then again changed loyalties.

According to the Republic Policy report, there are, however, signs of a gradual shift in the political landscape as political parties reclaim some of their lost ground.

The new outlet attributes it to rising urbanisation and increasing political awareness among the youth, who are less susceptible to the influence of traditional power brokers.

“The upcoming general elections will serve as a litmus test for this trend. Suppose political parties can successfully mobilise their supporters and defeat the electables in key constituencies. In that case, it will mark a significant step towards strengthening the party system and fostering a more ideologically driven political environment,” the report adds.

A concern for democracy

Certainly, it is a party’s right to select whichever candidate it prefers, and the length of affiliation with a political party cannot be the sole criterion on which tickets are handed out.

“While electables will emphasise patronage politics at the constituency level — the ability to remain a formidable constituency candidate depends on distributing patronage to supporters — they may not have a veto over a party’s policy, governance and reform agendas.

But no political party can reasonably claim to be strengthening its organisational structure while allowing large-scale lateral entry into the party. Weak political parties tend to weaken democracy as all party decision-making is concentrated in a few hands at the top,“ it says.

That may suit the party leaders, especially those who wield hereditary power, but it tends to weaken ties to the local party member or activist and thwarts democratic debate inside political parties.