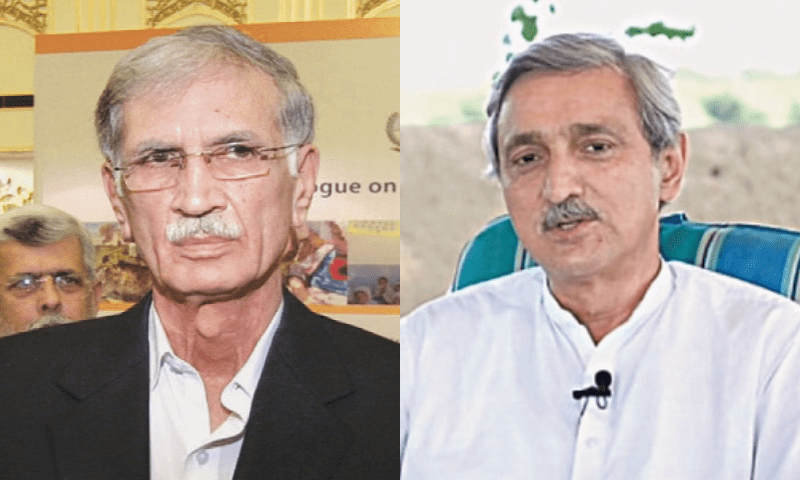

FUELLED by boastful claims that its leader is set to secure the chief minister’s slot following the February 8 general elections, Pervez Khattak’s Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf Parliamentarians (PTI-P), a breakaway faction of the Imran Khan-founded PTI, is vying for dominance in the bustling political arena of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

With the rumoured backing of the country’s powerful establishment, Mr Khattak is peddling his vision across public jalsas and private meetings. Yet, the PTI-P has struggled to attract the electables necessary to make Mr Khattak a formidable contender for the coveted position.

Despite events orchestrated to amplify the significance of each new joiner to Mr Khattak’s ranks, the reality is stark: electables are not flocking to the PTI-P as anticipated, leaving the party to scramble for notable candidates to field.

The party’s ambition is mirrored by the burgeoning force of Jahangir Khan Tareen’s Istehkam-i-Pakistan Party (IPP), another group birthed from the original PTI, navigating its first political storm in Punjab.

Its leadership had previously been part of Imran Khan’s party for over a decade, but was still ‘permitted’ to continue in politics and establish a political alternative to the PTI in the aftermath of May 9.

Those offering a new home to Imran Khan deserters have their own pre-election jitters; the IPP hasn’t managed to wrangle enough seats to accommodate its flock, while Khattak’s faction has scant electables to field, save for the party leader’s own kin

This was commonly perceived as happening due to the IPP’s leadership strong ties with the powers that be. At the time, the PDM was struggling under the burden of its own economically disastrous policies, putting its electoral chances in serious jeopardy. Adding to this, the self-exiled PML-N leader Nawaz Sharif was still considering his options upon his return and political future.

All these elements contributed to the formation of a new group of hopefuls, culminating in the birth of the IPP.

“When the PTI big bang happened on May 9,” Talat Hussain, a TV host and analyst, explains, “the splintering politicians were faced with three choices: leave the PTI, quit politics, or join a party they were directed to.”

The IPP fit this role, especially in Punjab. Since it symbolised the first significant split in the PTI under tumultuous circumstances, it became the preferred choice for those leaving the mothership. Its members, spared the harsh treatment meted out to others, naturally came to represent those dismantling the PTI, according to Mr Hussain.

‘Junior partner’ to PML-N?

However, the IPP finds itself wrestling with its own set of challenges. Despite its image as a group of wealthy, politically-savvy independents, it is grappling with its identity and the daunting task of asserting its significance in the post-poll power dynamics. The party is gingerly navigating the treacherous waters of political alliances and seat adjustments, often finding itself in the shadow of the larger and more entrenched PML-N.

When Nawaz Sharif returned and the PML-N regained its legal and political footing — positioning itself as the next head of the ruling clique in common political and electoral circles — the fortunes of the IPP fluctuated correspondingly. It appeared to be reduced to a junior partner. The PML-N expedited this process: leveraging its established position, it relegated the IPP to a role of a “dependent entity at its political mercy”.

With the post-poll scenario in mind and the IPP’s dreams of electoral relevance before them, the primary objective for the Nawaz League became to curtail its influence and diminish its post-poll significance. This opportunity arose as discussions on alliances and seat adjustments commenced between both establishment factions.

As negotiations began, according to IPP leader Ishaq Khan Khaqwani, his party requested 90 seats — 32 national and 58 provincial (Punjab). The PML-N initiated talks with an offer of around 30 seats, but then prolonged the negotiations, assessing how much support the IPP would receive and how much pressure the PML-N faced from concerned quarters.

With no active pressure applied and the talks left mainly to both parties, the initial alliance offer was withdrawn, and seat adjustment was limited to only 18 seats — seven for the National Assembly and 11 for the provincial assembly — where the PML-N agreed not to field candidates against IPP members.

In an attempt to further capitalise on its position, PML-N leaders alternated between condescending terms such as “gifting” and “accommodating” for the IPP and never publicly acknowledged the agreement between the two parties. The final blow to the IPP came when even party chief Tareen was not given a seat in his native Lodhran constituency, but instead allocated a seat in Multan. Consequently, the IPP saw its identity being absorbed by the PML-N, expected to be content with playing a secondary role, essentially being “accommodated on someone’s recommendation”.

The PML-N negotiated better, or the IPP inadvertently walked into its trap. The party would have been better off without such a political and electoral arrangement, which the PML-N refused to acknowledge even after extensive negotiations | Ishaq Khan Khaqwani, IPP leader

“Yes, the IPP’s image has taken a hit,” admits Khaqwani. He acknowledges that the PML-N negotiated better, or that the IPP inadvertently walked into its trap. Regardless, the outcome remains the same: the IPP is in a disadvantageous position concerning its electoral and political persona. Khaqwani suggests that the IPP would have been better off without such a political and electoral arrangement, which the PML-N refused to acknowledge even after extensive negotiations.

What fate awaits these factions?

In the backdrop of these unfolding narratives, the political landscape has been a chessboard of moves and countermoves. PTI-P, despite its initial optimism, realises the need to pivot its strategy, eyeing independent candidates to bolster its ranks post-elections. The party’s deep roots in the KP region, stemming from PTI’s previous reigns, has done little to quell the internal strife and public scepticism surrounding its electoral prospects.

Conversely, the IPP, despite the turmoil and looming shadow of PML-N’s dominance, holds onto a thread of hope. As the election draws near, party leaders cling to the belief that their political and electoral relevance would not wane, envisioning a scenario where they could tip the scales in the post-election power play.

Despite the condescending overtures from PML-N and diminishing seat adjustments, the IPP is not ready to be relegated to the sidelines.

In the thick of these political machinations, a few notable figures have spoken of the undercurrents shaping the fate of these emerging factions.

As rumours began circulating of the powers that be looking to put Mr Khattak in KP’s hot seat, unprecedented interference, allegedly on his part, began to be seen in the provincial government’s functioning.

“Mr Khattak has a big say in the posting and transfers of secretaries of government departments, deputy commissioners and district police officers,” a senior bureaucrat tells Dawn. Bureaucrats approach Mr Khattak to get lucrative posts in government departments, and after getting their desired positions, allegedly follow his directives. It is owing to this that Awami National Party’s KP president Aimal Wali Khan views Khattak as the de facto chief minister.

It is questionable, however, how the KP government’s reins can be handed over to Mr Khattak as it is hardly certain whether the PTI-P chairman or his vice chairman, Mahmood Khan, will even emerge victorious. The PTI-P has fielded its candidates on only 17 of 45 National Assembly seats allocated to KP and on only 73 of the 115 provincial assembly seats.

Notable among them are Mr Khattak, his two sons Mohammad Ibrahim and Mohammad Ismail, one son-in-law Imran Khattak, former chief minister Mahmood Khan, and former provincial ministers Ziaullah Bangash and Mohibullah Khan.

On top of this, the PTI popularity graph has further increased in KP owing to crackdowns on leaders and supporters of the party. Aggrieved PTI workers consider the upcoming polls an opportunity to vent their anger and seek to give a tough time to the PTI-P candidates for ditching Imran Khan.

Don’t write them off just yet

Meanwhile, when it comes to the IPP, political analyst Hassan Askari Rizvi notes that the PML-N went into negotiations with them “because it was told to”, but kept the seat adjustments to a bare minimum due to its own electoral compulsions. The complex interplay of cooperation and competition across various constituencies will ultimately unravel only after the election results are declared, he says.

IPP’s fortunes may yet see a turnaround in the post-election scenario, particularly if it performs well in the 192 parliamentary seats (51 in the Punjab Assembly and 141 in the national legislature) that it is contesting, either independently or with PML-N support.

If the IPP manages to secure 20 to 25 seats based on its electables and attract a dozen or so independent candidates, the total could reach around 35 seats — a decisive number when it comes to forming a government.

“It is too early to judge the IPP as a party, or to assess its political and electoral relevance,” says IPP president Abdul Aleem Khan. “The party will play a key role at both the federal and Punjab levels in the next government. We are contesting the elections on our own symbol, with seat adjustments in different national and provincial assemblies, and also competing against all other parties. We have a strong position in many of them. The next election will establish our place as a new political force.”

Despite these intricacies, one thing is for certain: the political stages of KP and Punjab are set for some interesting showdowns. Khattak’s rallies, though lacking the anticipated fervour, were a testament to his unwavering ambition, with his family members and loyalists like Mahmood Khan and Ziaullah Bangash standing firmly by his side.

On the other side, the IPP, with its contested alliance with PML-N and the ambitious claims of its leaders like Abdul Aleem Khan, is gearing up to assert its presence, refusing to be dismissed as a mere political footnote.

In this dance of power, influence, and ambition, the words of Mr Rizvi resonate as a reminder of the unpredictability of political tides: “Do not rule the IPP out till the post-election scenario unfolds.” The same sentiment echoes in the corridors of PTI-P, where hope still kindles against the odds.

With elections just days away, the people of both provinces watch with bated breath, knowing that the true measure of these parties’ strength and relevance will only be revealed in the aftermath of the polls, where the number of seats won will speak louder than the promises made.

Published in Dawn, January 30th, 2024

To find your constituency and location of your polling booth, SMS your NIC number (no spaces) to 8300. Once you know your constituency, visit the ECP website here for candidates.