In the Pashtun culture, women are still largely segregated into the domestic sphere because of constraining gender roles. But things are changing, slowly and subtly.

In the Bandagai village of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Dir district, the usual, perhaps monotonous, morning routine is broken by a hawker’s cry. “Walay tuki walay (buy fabrics),” echoes through the narrow lanes and sets off a flurry of activity.

As soon as the call, rising and falling in sing-song waves, makes its way inside the houses and through the kitchen walls, women of Bandagai leave every task to quickly run to their rooms and fetch money from all the hidden spots; cupboards, trunks, shelves.

As the hawker makes his way through the streets, his calls blend with the growls of stray dogs, creating a cacophony that could wake even the laziest of all. The hawker, tanned and wrinkled from years of trudging under the unforgiving sun, has gotten used to the clamorous reception.

There is quite a glow about him. His finely embroidered white topi and greying beard shimmers under the sun. A bundle of fabrics is slung over his shoulder, his figure stooped under its weight. The bundle sways left and right with every step, mimicking the surrounding wheat fields rustling in the breeze.

He soon gets hold of children playing hopscotch in the dirt nearby. “Go tell your mother I have brought new clothes … cheap and khaista (beautiful),” the hawker tells them.

Within a few minutes, an open-air market is set up nearby, subtly gendered. The everyday norms of purdah creep into the scene as stealthily as a jackal sneaks into a barn in the dead of the night and runs away with the chickens.

A rollercoaster of emotions

The hawker sits at a respectable distance from the house, out of which an elderly lady — often the Abai or Babbo (grandmothers) — walked out. Her old age and familiarity with the man have exempted her from purdah, which is otherwise non-negotiable. One could say that the elderly women are now more or less ‘degendered’.

In the absence of these grandmothers, children become messengers, scuttling between the hawkers and their mothers standing at the entrance of the homes, half-hidden. This arrangement, however, leaves women anxious; what if their husbands take exception to it?

Fortunately, it is mostly Babbo who steps out of the home to meet the hawker as he undoes his bundle after a few twists and tugs. Then comes an explosion of the neatly folded and carefully organised fabrics. Proud of his show, the hawker boasts of the fabric with hand movements as theatrical as the slow-motion replay of a wicket.

“Just arrived,” he announces, a confident smile tugging at the corner of his lips. “The house over there bought almost everything,” the hawker brags. “Just a few more pieces left.”

Unfazed by the man’s show-off, Babbo leans in, her eyes darting from fabric to fabric, a hunter spotting prey. She is a seasoned customer, shrewd and calculated, getting the right thing for the right price.

As the old lady picks and chooses, young women standing by the door in the nearby houses crane their necks to look at the exchange. Their fingers itch to touch the fabric. And when Babbo finally carries some samples up to them, they instantly jump at the opportunity, grabbing the tuki, feeling its texture, judging its weight and imagining how it would look stitched.

However, these are not the only factors that influenced the purchase. Ideally, the fabric had to be unique, something none of their relatives or friends have. And then, there is obviously the question of money.

Once the choices are made, the bargaining game begins. The hawker starts off with a high price, testing the waters and his luck. But as negotiations kick off, the offers come down. With years of experience and a commanding age, Babbo eases her way through these exchanges, victorious.

When it’s time to hand over the cash, she smoothes a bundle of folded notes with her palms and, with her lips moving silently, counts them twice, thrice, just to be sure that no single note is missing.

For some women in Bandagai, payments aren’t simple. They almost never have enough cash. So, the balance is settled later or paid in kind, sometimes with chickens or a goat promised to be sold and paid for later.

For others, the hawker’s visit spurred anxiety and stress. They run their fingers over the fabric, living a life they desperately want in their minds before returning it to the hawker. “Next time,” the women often say, more so to themselves. Perhaps, tomorrow would be slightly brighter when their chickens, goats or sheep grow fatter. Maybe then, they would have enough to buy.

The hawker, disappointed but empathetic, packs up his bundle and swings it over his shoulder. The weight of his unsold fabrics is not light, but no matter how many doors close, his steps do not falter. Off he goes to the next door, as he has done for decades, with his sing-song call: “Walay tuki walay.”

Stepping into the world of men

The scene described above was the lived experience for hundreds of women for as long as they can remember. In recent years, however, the tuki wala is fast becoming a relic of the past. No longer do the lanes echo with his booming voice. It’s not like he’s missed very much either.

Over the last decade or so, many women in Bandagai have begun to outgrow hawkers. They have been replaced by shopping spaces that are not just spacious, but also give women the agency to make purchases of their choice.

The first women’s shopping market was set up in the early 2000s near the graveyard in the Timergara Bazar. And, to no surprise, it wasn’t very well received by men, who dubbed it ‘Dozakh Market’ — an accusation and warning; a hotbed of evil influences, a descent into damnation. The space was seen as a place where women’s modesty and the masculinity of men who allowed them to go there were called into question.

These ominous remarks, however, did not hinder the growth of shopping spaces. Today, even small bazars feature rows of shops specialising in women’s clothing and other commodities.

(Re)negotiating social norms

For women in Dir, a shopping trip is often a family excursion, typically chaperoned by a male — sometimes a son, other times a not-so-eager husband. But recently, the village has seen a pleasant break from tradition — women shopping on their own.

It is no longer uncommon to see college and university girls, with their purses clutched in their hands, roaming independently through the market without a male escort. At times, they venture out in groups, tasting the freedom their grandmothers and mothers didn’t have. Most of them are rarely in a burkha; instead they choose to wear the much more comfortable paronay — a long chador or dupatta pulled around the head, body and face.

These girls take their time browsing and inspecting before making a decision. And while there are some spendthrift stories to tell later, the majority shop for needs. Women in the village don’t return home carrying armfuls of shopping bags because they still rely on men’s wallets — mostly stuffed with remittances from Gulf states.

I remember having a chat with Babbo once, who has seen the society evolve over the years. “Women today have so many clothes that their trunks are overflowing with them, yet they want to keep buying more,” she said.

In Pashtun culture, women are still largely segregated into the domestic sphere because of constraining gender roles. But things are changing, slowly and subtly, only if you look closer. One example is the sight of women in small villages, where the separation between home and public life was once strict.

These women tread cautiously, their gazes lowered, and their movements measured, but they are in the bazar now. There, they are more visible, asserting their presence, making choices, bargaining, buying and claiming a space in the male-defined sphere of the market. Over time, men have started making room in their world for their counterparts; the first sign of acceptance.

In cities, spearheaded by the younger generation of women, this change is much more visible.

More and more girls, with their backpacks on their shoulders, leave their homes each morning for school and university. They dare to envision a future beyond the kitchen, the yard, the walls and the farms. They step into ‘masculine’ territories by taking up jobs in schools, hospitals, and beyond. Through paid employment, they gain purchasing power. And with that comes something much more valuable: a voice, a choice and a sense of agency.

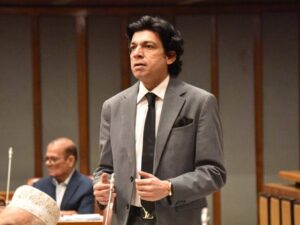

Header image: Women walk past Shafi Market in Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. — AN photo