With several legal and technical measures in the pipeline, this year may see Pakistani cyberspace being shaped in a way that conforms to the state’s idea of equilibrium, one where dissent and development are sacrificed at the altar of national security.

If the government’s claims are to be believed, the year 2025 will probably be a watershed for the country in terms of internet connectivity.

After all, infrastructure is being put into place to end Pakistan’s dependency on one of the world’s oldest submarine cables and connect it to the new AAE-2 (Africa, Asia and Europe) pipeline.

New legislation is also being rolled out: initiatives like the Digital Nation Pakistan Bill and ‘Uraan Pakistan’ project, the federal government push for e-governance methodologies and the digitalisation of government departments bodes well for those working in the online economy.

Ministers have also been quick to point out — in the face of criticism — that not only is the internet in Pakistan ‘faster and cheaper’ than most other countries, the number of its users has also grown exponentially, 25 per cent in the previous year alone.

But the problem is, no one is buying the official narrative anymore.

Like all other promises of yesteryear, the government’s actions belie its words and, so far, appear to be nothing more than positive spin.

In the context of internet governance, the year 2025 and beyond may see Pakistani cyberspace become more restricted than ever before, with both dissent and development being sacrificed at the altar of national security.

There were some upsides for those looking for a silver lining. For example, Pakistan’s median speed for both fixed-line connections and mobile data increased in 2024.

According to Ookla, which tracks the performance and quality of internet connections, the median mobile data speed was 16.67 megabits per second and 13.06mbps for fixed-line connections in November 2023. A year later, they increased to 20.89mbps and 15.53mbps, respectively.

This improvement was not a result of the government’s actions; it was in spite of them. Telecom companies and ISPs are investing in improving their infrastructure and increasing coverage areas, and this trend is expected to continue this year, especially if the underlying economic stability persists.

Another hope for things to improve is the government’s ambition for a “digital revolution”, which, unsurprisingly, would at least need a reliable internet connection.

ICT expert Tariq Mustafa told Dawn the only way things could improve is if the government realises that internet censorship and its plans like the ‘Uraan Pakistan’ and ‘Digital Nation Pakistan Bill’ are not mutually exclusive.

“The only hope is that their compulsion to improve the economy and bring investment would force them to change course,” he added.

Technical tampering

Attempts to throttle the internet aren’t a new phenomenon for Pakistanis, so why was their impact felt so profoundly this time around?

According to journalist Sindhu Abbasi, there are two reasons for this. The first is that internet penetration in Pakistan is now far greater than it was a decade ago.

“Even when YouTube was banned … there weren’t [that many] people monetising their content on the platform,” said Ms Abbasi, referring to the restriction on the video-streaming platform from 2013 to 2016.

Today, Pakistan is one of the fastest-growing markets for YouTube.

The throttling of the past also didn’t impact users as they weren’t heavily involved in freelancing and content creation on YouTube and other social media platforms, said Ms Abbasi, who has extensively worked on censorship, disinformation and cybercrime.

The second reason, she pointed out, was that this time, the government not only blocked internet services, but also the alternative means to access them.

“Previously, URLs were being blocked and apps being banned, [but] it wasn’t all out. … In the past, there was a certainty we knew YouTube was banned, but there were alternatives. Now, even alternatives have been blocked.”

Noose around social media

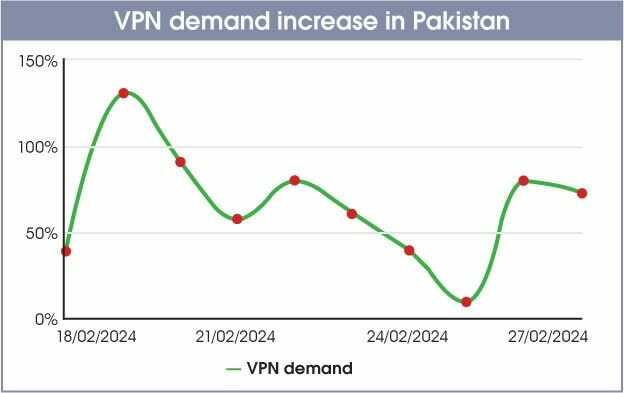

Much like other euphemisms that permeate the local vernacular — such as ‘loadshedding’ — the year 2024 gave us ‘firewall’, and, in the process, forced nearly every netizen to become an expert in the use of virtual private networks (VPNs) and anonymous browsing to get around restrictions on several websites.

The worst-hit were social media platforms such as X (formerly Twitter) — blocked ahead of the Feb 8 elections, but the restrictions were only formally acknowledged months later — and messaging apps such as the widely-used WhatsApp.

Past censorship had been like an imaginary red line: people knew what sites or services were blocked. They also knew that all else was working fine. That distinction was erased this time, and internet experiences varied, depending on where the user was based and how they chose to access the internet.

For example, while mobile data suffered greatly, broadband users had a comparatively easier time browsing the internet.

ICT expert Tariq Mustafa, who vividly remembers the internet throttling of the past, says back then, it was all or nothing — the internet would either be fully accessible or not. There were no in-betweens.

During the past year, the government tinkered with the nature of the internet, which is considered “holy” worldwide, he added.

“Whatever happened with the internet wasn’t [a total shutdown] … what was happening was that some services were accessible, some weren’t; some were loading fast, some slow. This is extremely troubling because you’re fundamentally taking away the internet’s reliability.”

This delicate balancing act did two things: it kept people guessing what the issue was and gave the officials plausible deniability.

Whenever the ban on X was brought up, the minister of state for IT’s rejoinder would be that only 2per cent of Pakistanis use the platform, and if the government actually wanted to curb free speech, they would have blocked TikTok, which had far more users than X.

The great ‘firewall’

The nation’s awakening to the internet firewall — a content filtration and monitoring tool — brought to mainstream the discourse about internet outages.

This was a silver lining, Ms Abbasi believes, as such outages were a norm in areas considered “strategic” by the state. It was only when these restrictions were mainstreamed that people started questioning them.

We still have no credible information from officials about what this filtration mechanism is and where it has been installed. We were only told that a ‘web management system’, which was already in place, was upgraded due to enhanced cybersecurity risks.

It was only through sources that we learned that the so-called firewall had been deployed at gateways from where the internet enters Pakistan. It was an advanced system capable of throttling and limiting content on an application basis.

The government did keep the workings of its filtration system a secret, but there was nothing secretive about how to bypass it — VPNs.

Research shows that on some days last year, VPN use in Pakistan surged by 102pc, 235pc, 253pc, 301pc and 342pc.

“Our people have faced so many challenges in the past that they have adapted to using alternates. When the internet got shut down, almost everybody started using VPNs,” said Mr Mustafa, the ICT expert.

The widespread adoption of VPNs neutralised the very purpose of the firewall. Hence, the purge against them became inevitable. The textbook of censorship was reopened with its tricks — from total shutdown of proxies to forced registration to national security concerns to licencing and even the ‘religious card’ — being used to lay the groundwork to stop VPNs.

Legal hoops

The fact that 2024 ended with VPNs still working is no mean feat, but it was simply due to the fact that the government wants to be on a firm footing when it finally pulls the plug on these proxies.

For now, the state seems to have shelved the plan to block VPNs due to legal hitches. The present law allows authorities to block content on social media, but VPNs are not content; they are tools to access content.

Now, there are plans to stretch the definition of content in a way that also includes tools used to access the content, hence giving a legal footing to any future ban on VPNs.

The year also started with the formation of the National Cyber Crime Investigation Agency (NCCIA) to “safeguard the digital rights of people and counter propaganda on social media”. The move threw up so many legal lacunae that the agency was effectively disbanded within seven months.

Only days later, officials floated the proposal for a new body, the National Forensics and Cybercrime Agency (NFCA), to tackle cyber and digital crimes and investigations. The body is planned to be set up under the NFCA Act 2024 to investigate crimes like “cyber fraud, hacking, cyber espionage, terrorism, online harassment and cyberbullying, cyber extortion and cyber warfare” and audio and video “deepfakes”.

Just before the year ended, another addition was made to this stack of authorities. The Digital Rights Protection Authority (DRPA), proposed in the draft amendments to the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016, would deal with issues such as the removal of online content, prosecuting people for sharing or accessing prohibited content and action against social media platforms where such content is hosted.

“It’s like a headless chicken. They don’t know what they want to do,” said Farieha Aziz, the co-founder and director at Bolo Bhi, a digital rights advocacy group.

“None of these legislative measures is actually for the benefit of citizens,” she pointed out, adding the government is trying to do different things under the pretence of drafting laws and “putting everything in writing” when actually they are “going more towards an authoritarian” rule by keeping the language of these regulations opaque and adding more red tapes.

‘No hope from court’

The internet censorship of the past evoked robust responses from the judiciary, something conspicuously missing throughout the past year.

This was visible during the ban on YouTube in 2013 and the Islamabad High Court’s (IHC) prompt intervention to strike down the amendment to Section 20 of Peca done by the PTI government in 2022.

Activists and civil society have filed multiple petitions in the Sindh High Court (SHC), Lahore High Court and the IHC over frequent internet outages in the lead-up to the general election, firewall and the months-long ban on X. However, the courts have shown no urgency in addressing these issues.

Lawyer and activist Jibran Nasir said this was a “complete and utter failure” of the judiciary as petitions over the internet outage have been pending for over a year and a half.

Mr Nasir, whose two petitions on internet outages were pending before the Sindh High Court, said this inaction by the judiciary gives rise to three perceptions: digital rights aren’t a priority for courts, or judges have made up their mind that even if they pass an order, it won’t be implemented by the government, or the judiciary is “colluding” with the executive by giving it time to put in place all its systems and then pass any order.

Ms Aziz concurred with these observations, adding: “They [courts] still look at social media in a hostile manner. One, they don’t understand it. Two, they look at it as something that should be tamed … because there is a lot that’s been said about the judiciary and they don’t necessarily like it very much. That element also comes into play consciously or subconsciously.”

She said courts didn’t take up these petitions for hearings and even when a matter was heard, only notices for responses were issued to the authorities. “There’s no sense of urgency or legal scrutiny of these actions by the PTA or the ministry.”

Pasha’s ‘blemished’ reputation

The Pakistan Software House Association (P@sha) has, over time, developed a reputation for being the leading stakeholder in any matter concerning the IT sector. The government routinely holds discussions with the group and takes its proposals into consideration, as demonstrated by the recent licensing scheme introduced for companies providing VPN services.

But background conversations with tech companies and those whose interests P@sha claims to be protecting have expressed disappointment with the group’s conduct throughout the last year.

They believe P@sha not only supported the government’s actions, but also offered justifications for them. One such statement by the group’s chairman — that a number of countries ask VPN providers to register locally — was even fact-checked by the media.

Both Ms Aziz and Ms Abbasi believe P@sha played a “negative” role on the issue of internet censorship.

“They just want to make the issue go away for themselves and the industry… That’s why they try to play a facilitation role for the government,” Ms Aziz added.

P@sha’s rise to prominence has coincided with the deliberate ostracising of digital rights activists by the government. This leaves organisations like P@sha, the Wireless & Internet Service Providers Association of Pakistan (Wispap) and the Pakistan Freelancers Association (Pafla), who could influence the government’s actions.

On their part, these groups criticised the internet firewall and internet disruptions, but their ability to strongly push back in the face of belligerent authorities is debatable as these representatives are in businesses regulated by these same authorities.

Ms Mustafa, the ICT expert, said P@sha representatives “rightly fear reprisals” if they vociferously oppose the government and that such considerations exist all over the world.

These groups have to work with the government, but there are some issues where “you have to take a stand and speak up,” he added.

Published in Dawn, January 15th, 2025

- Desk Reporthttps://foresightmags.com/author/admin/

- Desk Reporthttps://foresightmags.com/author/admin/

- Desk Reporthttps://foresightmags.com/author/admin/

- Desk Reporthttps://foresightmags.com/author/admin/