WASHINGTON:

Scientists using an ocean drilling vessel have dug the deepest hole ever in rock from Earth’s mantle – penetrating 4,160 feet (1,268 meters) below the Atlantic seabed – and obtained a large sample that is offering clues about our planet’s most voluminous layer.

This cylindrical core sample, researchers said on Thursday, is providing insight into the composition of the upper part of the mantle and the chemical processes that occur when this rock interacts with seawater over a range of temperatures. Such processes, they said, may have underpinned the advent of life on Earth billions of years ago.

The mantle, comprising more than 80% of the planet’s volume, is a layer of silicate rock sandwiched between Earth’s outer crust and ferociously hot core. Mantle rocks generally are inaccessible except where they are exposed at locations of seafloor spreading between the slowly moving continent-sized plates that make up the planet’s surface.

One such place is the Atlantis Massif, an underwater mountain where mantle rock is exposed on the seafloor. It is located in the middle of the Atlantic just west of the vast mid-Atlantic Ridge that forms the boundary between the North American plate and the Eurasian and African plates.

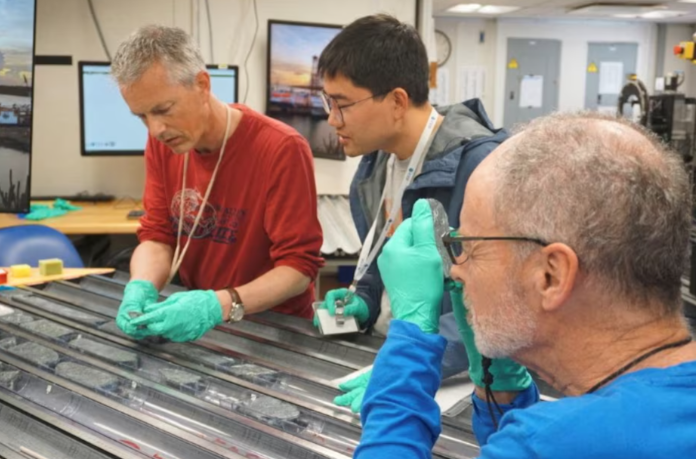

Using equipment aboard the vessel JOIDES Resolution, the researchers drilled into mantle rock about 2,800 feet (850 meters) beneath the ocean surface from April to June 2023. The core sample they recovered comprises more than 70% of the rock – 2,907 feet (886 meters) in length – from the hole they drilled.

“The recovery is record-breaking in that previous attempts of drilling mantle rocks have been difficult, with penetration no deeper than 200 meters (656 feet) and with relatively low recovery of rocks. In contrast, we penetrated 1,268 meters, recovering large sections of continuous mantle rocks,” said geologist Johan Lissenberg of Cardiff University in Wales, lead author of the study published in the journal Science, opens new tab.

“Previously, we have been largely limited to mantle samples dredged from the seafloor,” Lissenberg added.

The core sample has a diameter of about 2-1/2 inches (6.5 cm).

“We did have quite a bit of difficulty starting our hole,” said geologist and study co-author Andrew McCaig of the University of Leeds in England.

The researchers added a reinforced concrete cylinder lining to the uppermost part of the hole, McCaig said, “and then drilled unexpectedly easily.”

They documented how a mineral called olivine in the core sample had reacted with seawater at various temperatures.

“The reaction between seawater and mantle rocks on or near the seafloor releases hydrogen, which in turn forms compounds such as methane, which underpin microbial life. This is one of the hypotheses for the origin of life on Earth,” Lissenberg said.

“Our recovery of mantle rocks enables us to study these reactions in great detail and across a range of temperatures, and link it to the observations our microbiologists make on the abundance and types of microbes present in the rocks, and the depth to which microbes occur beneath the ocean floor,” Lissenberg added.

The drill site was located close to the Lost City Hydrothermal Field, an area of hydrothermal vents on the seabed spurting super-heated water. The core sample is thought to be representative of the mantle rock beneath the Lost City vents.

“One suggestion for the origin of life on Earth is that it could have happened in an environment similar to Lost City,” McCaig said.

The core sample is still being analyzed. The researchers made some preliminary findings about its composition and documented a more extensive history of melting – molten rock – than expected.

“The mineral orthopyroxene in particular showed a wide range of abundance on a range of scales, from the centimeter to hundreds of meters,” Lissenberg said. “We relate this to the flow of melt through the upper mantle. As the upper mantle rises up beneath the spreading plates, it melts, and this melt migrates up towards the surface to feed volcanoes.”