LAHORE/KARACHI/PESHAWAR:

The birth of a child is typically seen as a happy occasion, with numerous rites and rituals celebrating the miracle of life. However, such is not the case for nearly 42 out of every 1,000 parents across the country who, in the absence of adequate neonatal intensive care units (NICU’s) often have to anticipate the grim possibility of burying their own child.

Similar were the fears of Ahmed’s parents, who had to travel nearly 400 kilometres by road before they could seek treatment for their son’s cardiac ailment at the Children’s Hospital in Lahore. Ahmed’s mother revealed that the shortage of treatment facilities in their own area for neonates had prompted their family to travel to Lahore. “We are based in Lodhran. Since there are no such facilities in Southern Punjab, doctors in Multan referred us to this hospital,” revealed Ahmed’s mother.

Like Ahmed’s mother, thousands of other anxious parents and grandparents were spotted pacing across the corridors of the Children’s Hospital, which is the only paediatric tertiary facility for children in the country’s most populous province, Punjab, which is home to nearly 56 million children. One such caregiver was Naziran Bibi, a woman hailing from Kasur, who was accompanying her ailing grandson. “The baby is in a critical condition. Therefore, we had to bring him here for specialized care,” said Naziran from the Children’s Hospital, where three to four children often share a single bed.

“Although the Children’s Hospital is equipped with modern and comprehensive paediatric facilities, the heavy patient load has led to overcrowded conditions and a shortage of nursing staff and doctors. Despite the hospital’s recent renovations, the nursery ward, emergency unit, and NICUs continue to experience overwhelming demand,” confirmed Professor Dr Muhammad Junaid, Chairman of the Department of Paediatrics at the Children’s Hospital, which has only 100 ventilators and 1,300 beds available for over 2,000 children arriving at the hospital for emergency medical care on a daily basis.

Dr Salman Kazmi, General Secretary of the Young Doctors Association (YDA), was of the opinion that the facilities at the Children’s Hospital, which has now become a teaching hospital, should be improved by enhancing the capacity of the ICU and emergency ward. “Furthermore, paediatric wards with trained doctors and nurses should be established at the district headquarter hospitals (DHQs). Since many of our doctors are working abroad, our hospitals lack medical professionals,” observed Dr Kazmi.

The problem was no less severe in Sindh, where except for a few large government hospitals in Karachi, most healthcare facilities had no arrangements for a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), presenting a conundrum for families who lacked the finances to seek help at costly private hospitals.

According to Professor Dr Jamal Raza, a paediatrician, out of 250,000 deliveries that occur annually in Sindh, 10 percent end up with the baby requiring specialized neonatal care at an NICU.

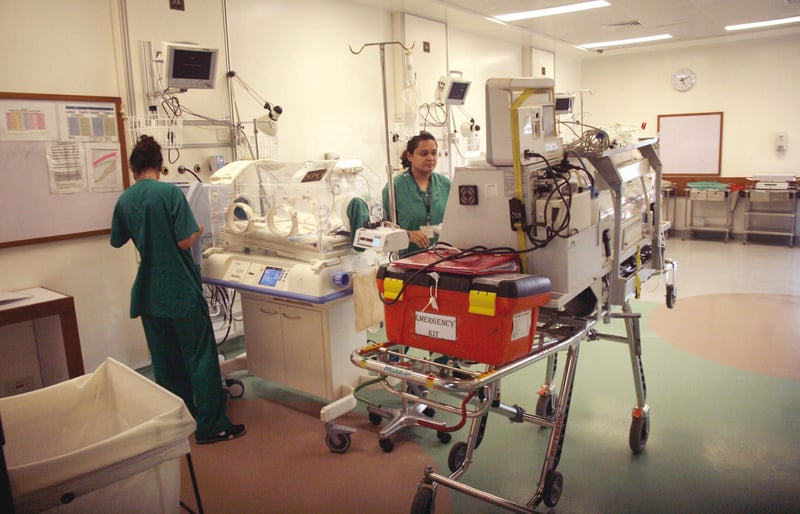

“Malnutrition in the mother, lack of prenatal care and the high incidence of unsafe home births in rural Sindh are one of the primary factors leading to the development of neonatal complications. Even in urban areas, deliveries often take place in small hospitals, which lack an incubator facility. Babies born with low birth weight are particularly in need of incubators,” said Dr Raza, who revealed that currently there were 75 incubators at NICH, 36 incubators across six different children’s wards at the Civil Hospital Karachi and 52 incubators at the Sindh Institute of Child Health.

“A newborn baby needs an incubator immediately after birth in three specific cases. The first scenario concerns babies who are born prematurely- before the 37th week of pregnancy. The second involves those infants who weigh less than two and a half kilograms at birth while the third case concerns babies who develop some health complication after birth. In all such cases, an incubator is required immediately after birth to save the babies’ lives,” explained Dr Rahat Naz, Pediatrician and Director Human Resource at the Jinnah Sindh Medical University.

According to Dr Naz, an incubator, which is the specialized equipment required inside a NICU, regulates the temperature and oxygen supply to the newborn alongside using phototherapy to save their life. “Private hospitals charge a daily fee of Rs20,000 to Rs40,000 to keep a newborn in an incubator,” noted Dr Naz, who believed that promoting regular prenatal check-up and a safe delivery for the mother alongside ensuring the presence of an incubator and paediatrician for the baby could help save the lives of infants snuggled by death.

In the country’s snowcapped region of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, although the exact shortage of NICU facilities was hard to gauge given the lack of attention given to maternal and neonatal health, the gravity of the problem was evident in the province’s alarming neonatal mortality rate which, at 53 infant deaths per 1,000 births, was higher than the national average by 32.5 per cent.

Professor Dr Muhammad Hussain, President of the Pakistan Paediatric Association K-P, highlighted the critical gaps in neonatal care in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (K-P). “The government’s failure to provide advanced healthcare facilities for infants, such as NICUs, has significantly contributed to the region’s alarmingly high neonatal mortality rate, which is among the highest globally. Shockingly, much of K-P lacks qualified neonatologists, except for Swabi. Moreover, there is an acute shortage of trained neonatal care nurses in both the public and private sectors. This situation underscores the systemic neglect of maternal and newborn health in the province,” said Dr Hussain, who believed that although initiatives like the Umeed-e-Nau project by AKU alongside those initiated by international donors had improved maternal and neonatal health nationwide, K-P remained largely excluded.

“NICUs are critical for saving the lives of infants. Although Peshawar has such units at the Khyber Teaching hospital, Hayatabad Medical Complex and Lady Reading Hospital, the remote areas of K-P still have no specialized NICUs for ailing infants. K-P even lacks a dedicated hospital for treating the health conditions of children. Even when some places have a NICU available, the nursing staff is often not trained, which endangers the life of the infant,” confirmed Dr Hamid Bangash, a neonatal specialist.

Dr Bangash’s revelations underscore the importance of trained NICU staff for saving the lives of neonates, who are hanging indefinitely between life and death. According to UConn Health, a US-based hospital, neonates have an underdeveloped immune system while premature babies especially have a harder time fighting off germs, which increases their likelihood of catching an infection and falling extremely sick. Therefore, all staff at the NICU must adhere to strict hand hygiene protocols by watching their hands up to their elbows for three minutes with an antibacterial soap before attending to an infant.

“Infections are the primary cause of neonatal deaths in the country apart from premature birth, respiratory problems and other complications. As a result, since the past two decades, the neonatal mortality rate- death within the first 28 days- could not be controlled in Pakistan. Even today, at least 40 out of every 1,000 infants die due to various complications,” concluded Dr Raza, former Director at the National Institute of Child Health (NICH).

Similarly, in Balochistan, the largest province, neonatal care facilities are barely adequate to meet the needs of infants. According to details gathered by The Express Tribune, many newborns with serious conditions are transported to Karachi for medical treatmentsome do not survive the journey. A recent study reveals that, despite being the least populated, Balochistan bears the highest neonatal mortality burden, with 63 deaths per 1,000 live births.