Triumph, rather than tragedy, is the first word that comes to mind when an ordinary Pakistani thinks of Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah. Striving against formidable odds, he gifted us, through his extraordinary leadership, an independent, Muslim-majority nation-state.

Yet his life, from his birth in 1876 to his demise in 1948, was also marked by much tragedy. He repeatedly suffered setbacks to his equanimity at different points in time. Though his capacity to absorb sudden shocks helped him overcome them all, these events merged, by gradual accretion over the decades, into a singular, tragic dimension of his legend towards the end of his life. This is an aspect of Mr Jinnah’s life that contrasts starkly with the public acclaim he is usually associated with and one that has not been explored enough.

13 months, not 13 years

Possibly the greatest tragedy suffered by Mr Jinnah was the extremely short period he got to build on his greatest achievement: Pakistan. After Independence, Mr Jinnah only had 13 months to savour victory, or a little over one year. That, too, in severely impaired health and at an incredibly tumultuous time.

In comparison, the founding fathers of an assortment of countries across the world were able to continue their nation-building exercises for many years after their countries emerged as independent nation-states. Though Mohandas Gandhi was assassinated within seven months of India’s independence and he never held public office, Jawaharlal Nehru served as the first prime minister of India for a good 17 years, ensuring continuity and stability post-independence. Shaikh Mujibur Rahman retained his office for over three and a half years before his assassination in August 1975. D.S. Senanayake in Sri Lanka steered his island nation as its first prime minister from 1947 to 1952. Decades earlier, Vladimir Lenin led the Russian Revolution and established and ruled the giant USSR for seven years, from 1917 to 1924. About a century and a quarter earlier, George Washington pioneered America’s history for 23 years, from 1776 to 1799.

In Latin America, the phenomenal Simon Bolivar, regarded as the founder of six independent states — Venezuela (his birthplace), Colombia (where he passed away), Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru and Panama — lived on for about 19 years after the formation of Venezuela in 1811. In Africa, Jomo Kenyatta, the first president of Kenya, held office for about 14 years from 1964 to 1978. Further north, in Egypt, Gamal Nasser became president in 1956, just four years after its independence, and continued as president for 14 years till his demise in 1970.

In Eurasia, Turkey was transformed from “the sick man of Europe” into a dynamic new force under Mustafa Ataturk’s leadership from 1923 to 1938. In Europe, West Germany gained from the leadership of Chancellor Konrad Adenauer for 14 years, from 1949 to 1963. Shaikh Zayed guided the UAE for 33 years from 1971 to 2004. Almost for the same length of time, Lee Kuan Yew changed a micro-state into a global force, leading Singapore for 31 years between 1959 and 1990.

Next door, even though for less than half that tenure, Tunku Abdur Rahman, Malaysia’s first prime minister from 1957 to 1970, set his country in a fine, steady direction. As Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno welded 15,000 islands together over 22 years from 1945 to 1967. In China, Mao Tse Tung overcame upturns and upheavals for 27 years from 1949 to 1976.

The many setbacks the Quaid-i-Azam faced over the course of his life merged, by gradual accretion over the decades, into a singular, tragic dimension of his legend that does not seem to be discussed as much.

How would any one of the above nations have fared if these illustrious figures had been given only 13 months? As to what M.A. Jinnah achieved even before his untimely demise, let the concluding paragraph of this reflection express the truth. For now, let us go back to his early years of personal struggle.

Arranged marriage, new freedoms

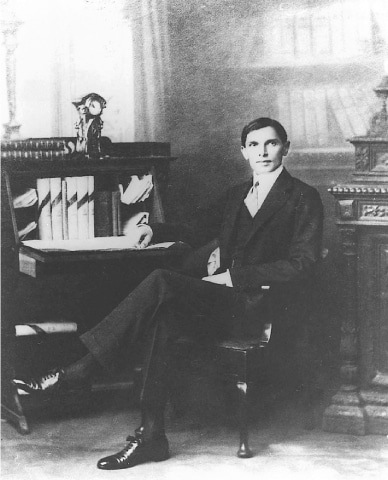

Married to Emi Bai at only 16 years of age in 1893, as a precondition for his passage to London — where he was to learn about finance and accounting before returning to help grow his father’s business — the young M.A. Jinnah must surely have departed with more than a twinge of regret. He was to leave his bride for what would be a prolonged, three-year absence without getting to know her even cursorily.

Once in the capital of the British Empire, the law and the stage attracted him far more than the ledger, and even after he was called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn, it seems that theatre remained his actual passion. He even signed a contract with a company to serve as an actor. Shakespeare, and Romeo in particular, reportedly fascinated him. But when his father received a letter informing him of his son’s radical new plans, a quick, angry remonstration compelled a reversal. It was fortuitous that the theatre company was understanding and relieved him of the agreement he had signed requiring a three-month notice period.

Surely, this triple turn-around pricked him with a sharp pain: from dull but profit-promising accounts to a fascination for make-believe, for the theatre — and then to the obfuscations of legalese. The only consolation may have been the scope for dramatic, captivating interludes in court arguments.

Two more blows followed: messages about the loss of both his doting mother and his wife within weeks of each other. One, a woman who loved him so dearly; the other, a young woman he knew little, but one he must have looked forward to knowing, and perhaps even to love?

So bleak was the news from Karachi that M.A. Jinnah seems to have decided to turn away from the city of his birth. His self-imposed exile would last for at least the next four decades. The ability to suffer without visible upset must have matured in him at this relatively early stage. The acquisition of Saville Row suits as standard wear and the cultivation of a deliberate, unruffled calm to imitate that quintessentially English trait of impassivity must have helped conceal, but not entirely delete the distress or abjure it from memory.

Before leaving London in 1896, he opened a bank account in Bombay and, soon after arrival there, began a new, uncertain legal practice with a scarce clientele. The struggle continued until his almost chance appointment to a junior magistracy. This opportunity enabled him to learn how to justly render a solemn public responsibility. It also gradually led to success in the legal sphere as a private practitioner.

Swift exposure to political heat

From active membership of the Home Rule League to his resignation and a parting of ways with its avid leader, Annie Besant, to the awkward position of opposing the Khilafat Movement — which had curiously united both the fervently Muslim Mohammad Ali brothers and the proudly Hindu Mohandas Gandhi, under the unrealistic aim of sustaining a decaying Muslim Ottoman Caliphate, theoretically for the entire Islamic Ummah — these contrary positions taken and arduously advocated could only have stirred inner discomfort and distraction.

The unsettling recurrence of disagreements with Gandhi in particular, a foreboding that the negative — not the positive — facets of religion were being introduced into political discourse via the call for a civil disobedience movement (which ultimately proved to be a failure, as he correctly foresaw), aggravated Mr Jinnah’s apprehensions. Participation in the end-1920 session of the Congress in Nagpur, where about 14,000-plus delegates loudly booed him for his refusal to address Gandhi as “Mahatma”, surely cut him to the bone, a wound that the passage of time alone could not heal.

Ten years of tumult, 1918-1928

From the public to the personal realm, both euphoria and angst were to follow — initially in consecutive sequence, and then simultaneously.

Mr Jinnah had fallen head over heels for a girl seen as ‘the most beautiful’ in most people’s eyes, including his own. Ruttie Petit, a Zoroastrian, was almost half his age, and he had to wait for her to turn eighteen before being able to wed her. Their union inspired Ruttie to break with her loving father and mother, her sacred religion, her close community and her fond friends. The ten-year span of Mr Jinnah’s married life with Ruttie featured, at one extreme, the fearless, thrill-filled breaking of taboos, and at the other, only relatively brief times actually shared with her after long weeks of separation and forlorn yearning.

Though Mr Jinnah was engaged in a worthy public cause — pursuing self-rule, autonomy, and eventual freedom from colonial reign, while also continuing his lucrative legal practice — could his inability to spend more time with her, to reciprocate the abundant adoration she bestowed on him, have turned into guilt which he preferred to ignore, or set aside too often? There was also the knowledge that it was she who had made enormous, excruciating sacrifices for him, whereas he barely had to make any sacrifice for her. This made it a grossly unequal, unfair pairing. Her growing dependence on pills, drugs and spiritual searches to numb her nerves dragged her down into the abyss — even as he strove to reach new summits of public support. Because he maintained the visage of imperturbability and never wrote or spoke candidly about their relationship, are the true answers forever lost?

The torment must have gone deep — except, and alas, too late, when he helped place Ruttie in her last resting place in February 1929. This was certainly a burden of profound remorse he bore in silence for the next twenty years of his own life. Ruttie’s loss created a vacuum that was never again to be filled by another woman — an abiding, fearsome emptiness which even the adoring companionship of his sister, Fatima, up to the very end, could never fulfil.

Conjoined almost cruelly with the grievous shock of Ruttie’s demise was the irony that eventually came years later: his refusal to accept the decision of their only child, Dina, to marry a Zoroastrian — though this is exactly what he himself had done — only to belatedly realise that it may be easier to be a father to a whole nation than to be one to his own daughter and only child.

A new horizon

After the fruitless outcomes of the Round Table conferences in London, followed by his self-exile to that same city in the early/mid-1930s, he was obliged to make a fateful choice by 1937. He had to choose between continued pursuit of a singular new entity in South Asia that could merge British-ruled Hindu-majority and Muslim-majority provinces with 565 princely states, or adopt a path which may eventually lead to a separate, sovereign, Muslim-majority homeland.

In finally accepting in his own mind that all his earnest wishes to preserve Muslim-Hindu unity had become delusional in the face of the Congress Party’s intransigence on the recognition of the reality of Muslims embodying a distinct national status and not just a religious minority, M.A. Jinnah must have experienced intense internal turmoil. He was forced to banish once and for all the notion of peaceful co-existence of two starkly different communities, which nevertheless practised mutual respect for respective rights and responsibilities — a notion that he had propagated vigorously for over thirty years.

The well-considered transition of personal attire in 1937 at the Lucknow session of the Muslim League was quite likely to have been more than a change of garments alone. To bring his aloof, western-looking persona closer to the ideal public visage of indigenous Muslim wear, he changed his wardrobe of elegant, tailored English-style suits and bow-ties to add equally elegant, but thoroughly eastern Muslim sherwanis/achkans and shalwars — to be topped off with a cap that came to be called after his own name.

An unresolved dilemma

In the next ten years, as he steered the so-far elitist Muslim League towards a more grass-roots, proletarian ethos with more penetrative organisation at the district levels — a move which would culminate in the sweeping electoral victories of the 1946 elections — Mr Jinnah began to confront the bedevilling question of how the creation of Pakistan in Muslim-majority provinces would address the future security of fellow Muslim religionists in Hindu-majority provinces and princely states.

The thesis was advanced that non-Muslims in the Pakistan-bound provinces would serve as counterweights and guarantees of security for Muslims in Hindu-majority areas. But, as communal riots and violence even before mid-August 1947 began to show, the thesis first began to be questioned and then was outright rejected. The extent of Mr Jinnah’s disquiet, even beyond what he publicly stated, can be well-imagined — and the worst was yet to come.

Vitriol and violence

Despite being accustomed to declaring a viewpoint that went against populist narratives being pushed by others, the Quaid could not possibly have taken the derogatory, almost abusive label of being termed “Kaafir-e-Azam” without feeling anguish. The pain must have been made all the sharper by it being bandied by fellow Muslims who opposed the creation of Pakistan. Though he handled with aplomb and courage the fortunately unsuccessful attempt on his life in Bombay in 1943 by a knife-wielding Muslim assassin from the Khaksar Tehreek, it must have seriously troubled him to glimpse the hatred his political position could arouse.

With ecstasy, agony

With his reluctant acceptance of the shoddily prepared, irrationally hasty plans imposed by Viceroy Mountbatten who, on June 3, 1947, gave the absurdly short notice of ten weeks for the establishment of two new states, targeting independence by mid-August 1947, any qualms the Quaid had were concealed under a cloak of calm essential for the sole supreme leader. Meanwhile, the bloody carnage accompanying panicked transfers of population had already commenced.

The viceroy’s refusal to accept his own Supreme Commander Auchinleck’s recommendation to effectively deploy British troops for security duties tested M.A. Jinnah’s patience to the nth degree, in a phase when his health was deteriorating by the day. This was a race against time.

With freedom, fatigue and fury

Eventually, so evident had the frailty of his physical aspect become that, during the latter part of a reception hosted at the Governor-General’s residence in Karachi on the evening of August 14, 1947, the Quaid asked his ADC to quietly convey to the viceroy that His Excellency should depart from the event at the earliest. Mountbatten appeared to be enjoying himself so much that he was testing his host’s patience and, more importantly, his health. Mountbatten promptly took his leave and later emplaned for New Delhi to preside over India’s birth as a state the next day.

The photograph of the Quaid with Fatima Jinnah that evening reveals a disturbingly emaciated figure who was quietly bearing the agony of his dwindling energy while taking receipt of reports of rapidly increasing violence in Punjab.

After the glory of the first few days of Independence came the sour, stringent poison of the Radcliffe Award, almost perversely delayed by Mountbatten, ostensibly to prevent controversy and strife before mid-August. The outrageous allotment of the Ferozepur headworks to India, the blatant disregard of the Muslim majority in Gurdaspur — to enable Indian access by land to Srinagar — obviously aggravated the Quaid’s condition, made all the more enervating because all parties had agreed in June to accept the Boundary Award without challenge, to prevent the eruption of new conflicts post-Independence.

The terrible trio

Between August 14, 1947, and September 11, 1948, in almost simultaneous lock-step, unfolded upon his being the terrible trio of tragedies that defined the final thirteen months of his life.

First: the frenetic proliferation of pressures — excesses of bloodshed; shortage of shelter for millions of refugees; the sadistic refusal of India to remit Pakistan’s due shares of funds, equipment and armaments already agreed upon; the fraud of the Kashmiri maharajah’s accession to India and the eruption of armed conflict in the Valley. Second: the inability of his colleagues in the cabinet and in the Muslim League, notwithstanding their sincerity and devotion, to provide the extraordinary efficiency, imagination and innovation needed in unprecedented conditions. Third: his steady, unrelenting loss of stamina and energy even as he set aside acute stress to travel to Peshawar, Dhaka, Lahore, and also attend important events in Quetta and Karachi.

At 50 cigarettes a day for decades, M.A. Jinnah’s lungs and body were close to a final collapse. Neither Ziarat nor Quetta nor ministrations by the medical team led by Colonel Illahi Buksh could reverse or halt the rapid decline in his health in early September 1948. Despite his instructions not to inform the prime minister or the cabinet about his final journey to Karachi on the afternoon of September 11, it is inexplicable as to why and how the air travel in a special plane by the head of state in a critical health condition could be kept a secret. The mystery is compounded by Col Buksh’s son’s claim that sections of his father’s memoirs dealing with the founder’s last days were removed by the government before their publication was permitted. Will we ever know?

Mr Jinnah was greeted at the Mauripur airfield by only his military secretary, an ambulance and a Cadillac car. The governor-general then had to bear intense discomfort, the heat and flies when his ambulance broke down after travelling only four miles. It took almost an hour to fetch another ambulance, as the car could not carry the stretcher he was resting on.

And thus were spent the last few hours of one of the greatest men history has produced: helpless and without aid in the country he had created.

Though alive for only 13 months after he crafted the miracle of Pakistan, the Quaid surpassed many of those who lived long after their respective countries gained their independence. The opening four sentences of Stanley Wolpert’s biography, Jinnah of Pakistan, best express the magnificence of his work:

“Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a nation-state. Mohammad Ali Jinnah did all three.”

The writer is an author and a former senator and federal minister. He can be reached at javedjabbar.2@gmail.com