Seven judges of the Islamabad High Court (IHC) on Friday penned a letter to the chief justices (CJ) of the Supreme Court and high courts, urging them to take a stand against reports of a transferred judge being appointed to the IHC’s top seat and to resist such a development.

Dawn reported last month that the judicial bureaucracy is reportedly planning to bring a judge from the Lahore High Court (LHC) to lead the IHC after the incumbent CJ’s elevation. According to sources, another judge from the Sindh High Court (SHC) may also be transferred to the IHC.

Traditionally, the senior puisne judge of a high court is appointed as the chief justice, but the Judicial Commission of Pakistan (JCP) earlier this year introduced new rules to bypass the seniority criterion in light of the 26th Amendment. The JCP proposed that the chief justice of a high court could be appointed from among the panel of five senior-most judges.

Today’s letter, seen by Dawn.com, on the above reports was addressed to CJP Yahya Afridi and the top high court judges of Islamabad, Sindh and Lahore.

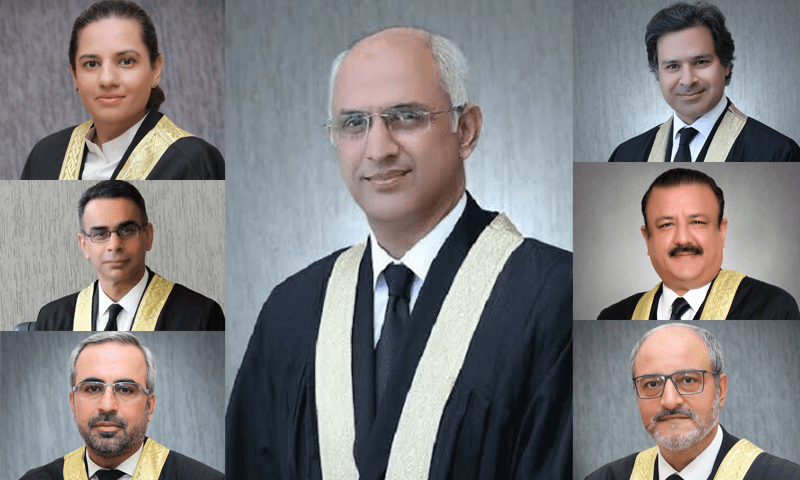

The letter was signed by IHC’s senior puisne judge Justice Mohsin Akhtar Kayani and Justices Tariq Mehmood Jahangiri, Babar Sattar, Sardar Ejaz Ishaq Khan, Arbab Muhammad Tahir, Saman Rafat Imtiaz and Miangul Hassan Aurangzeb.

The judges urged the four chief justices to advise President Asif Ali Zardari to not allow any such transfer as being reported since there was no conception of a unified federal judicial service in Pakistan under the existing scheme of the Constitution.

“The high courts are independent and autonomous. The justices who are elevated to a particular high court, take oath, under Article 194 of the Constitution, with respect a particular province, or for the purposes of the IHC, with respect to the Islamabad Capital Territory. Since the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 2010, and during the times of political democratic governments in Pakistan, there has been no precedent of permanent appointments to the high courts through the invocation of Article 200 of the Constitution,” the letter said.

It said the 26th Constitutional Amendment had not institutionalised the transfer mechanism for high court judges from one to another as was originally proposed in the drafts of the amendment.

It said that despite a major overhaul to the judicial framework under the 26th amendment, the legislature did not allow for permanent transfers to become constitutionalised as envisaged in the proposal.

“Article 200 did not undergo any changes. The conception of each court being separate and autonomous, under the system of federalism, has remained intact.”

The letter said that the purpose of the LHC judge’s alleged transfer was reported to be a consideration for the IHC’s top post, adding that this “just cannot be under the Constitution”.

It argued that the transferred judge would need to take a fresh oath under Article 194 of the Constitution, for serving in a new high court and thus their seniority would be determined from the date of the oath for the purpose of serving at the IHC.

The letter pointed out that the Supreme Court had already held that the seniority of a judge was determined from their oathtaking date at the high court they were to serve at.

“Hence, a transferred judge, required to take a fresh oath, would be at the bottom-end of the seniority list, at the date of such transfer, despite his prior service at another high court. The transferred judge, as a result, may find such a situation to be unfortunate, which, may, in turn, lead to friction, jeopardising the smooth functioning of the court.”

The letter further termed the alleged purpose for a LHC judge’s transfer as a “fraud on the Constitution”, arguing that once judges were appointed to a high court, only the three senior-most justices of that court were to be considered for the position of the chief justice.

“It defeats the purpose of the Constitution and the 2024 Appointment Rules, if a judge, otherwise lower down in seniority in another high court, is then introduced as a transferred judge, to be then considered and appointed as the chief justice in the court to which he is transferred,” the letter said.

It continued: “In the instance that such transfers from one high court to another high court are allowed, on a permanent basis, particularly for taking the position of the chief justice, then this would be detrimental to the basic, foundational conception undergirding the Constitution, that of independence of the judiciary. This would provide an opportunity, to select a judge from one high court and introduce that judge in another high court, for the purposes of exercising control over that high court, as the chief justice.

“A high court, with its own inter-se seniority, would become amenable to control by a judge, otherwise alien to that court. This would have widespread consequences particularly how the judiciary views its role under the Constitution, setting up perverse incentives of ingratiation for the judges.”

The judges also assailed the suggested reason for such a transfer as being one of pendency in the IHC’s cases or empty occupancies for judges, pointing out that the LHC’s figures had a worse showing in both regards.

“In sum, there is no facially plausible public interest that would be served by undertaking the transfer,” the letter added.

It further argued that the appointment of a judge to a high court was the prerogative of the JCP under the Constitution and if there were vacant seats, for which eligible candidates were to be considered by a collegiate body, that function function could not be taken over by invoking Article 200 of the Constitution.

The judges said that doing so would be “tantamount to usurping the role of the Commission”, pointing out that the JCP recently had the opportunity to fill the four vacant seats at the IHC but chose to fill two instead after much deliberation over a large number of candidates.

“Filling in other seats by invoking Article 200 of the Constitution would be nothing but short-circuiting the constitutionally provided mechanism of appointing judges.

“It is for the above reasons, therefore, that it is requested to the honourable chief justices that in their consultation with the president, under Article 200 of the Constitution, it be categorically presented that such a permanent transfer of a judge to the IHC would be against the spirit of the Constitution, detrimental for the independence of judiciary, usurpation of established judicial norms and also wholly unjustifiable. It would set a pernicious precedent whose ramifications are going to be extremely far-reaching,” the judges cautioned.

According to sources, Justice Sardar Mohammad Sarfraz Dogar of the LHC is likely to be transferred to the IHC. Justice Dogar was appointed as a judge of the LHC on June 8, 2015.

Upon his transfer, Justice Dogar will become the senior-most judge of the IHC until IHC CJ Aamer Farooq’s elevation to the Supreme Court.

In the IHC, Justice Mohsin Akhtar Kayani is the senior puisne judge, who was appointed on Dec 23, 2015. Other judges in the seniority order are: Justice Miangul Hassan Aurangzeb, Justice Tariq Mehmood Jahangiri, Justice Babar Sattar, Justice Sardar Ejaz Ishaq Khan, Justice Arbab Mohammad Tahir and Justice Saman Rafat Imtiaz.

Justice Dogar is being transferred under Article 200 of the Constitution which says: “The president may transfer a judge of a high court from one high court to another high court, but no judge shall be so transferred except with his consent and after consultation by the president with the chief justice of Pakistan (CJP) and the chief justice of both the high courts.”

According to the JCP rules, following his transfer, the name of Justice Dogar will be included in the panel for the proposed chief justice. A few judges of the IHC have already expressed their concerns to the CJP over the transfer. However, the sources claimed that the formal process for the posting of Justice Dogar had already begun.

- Desk Reporthttps://foresightmags.com/author/admin/